|

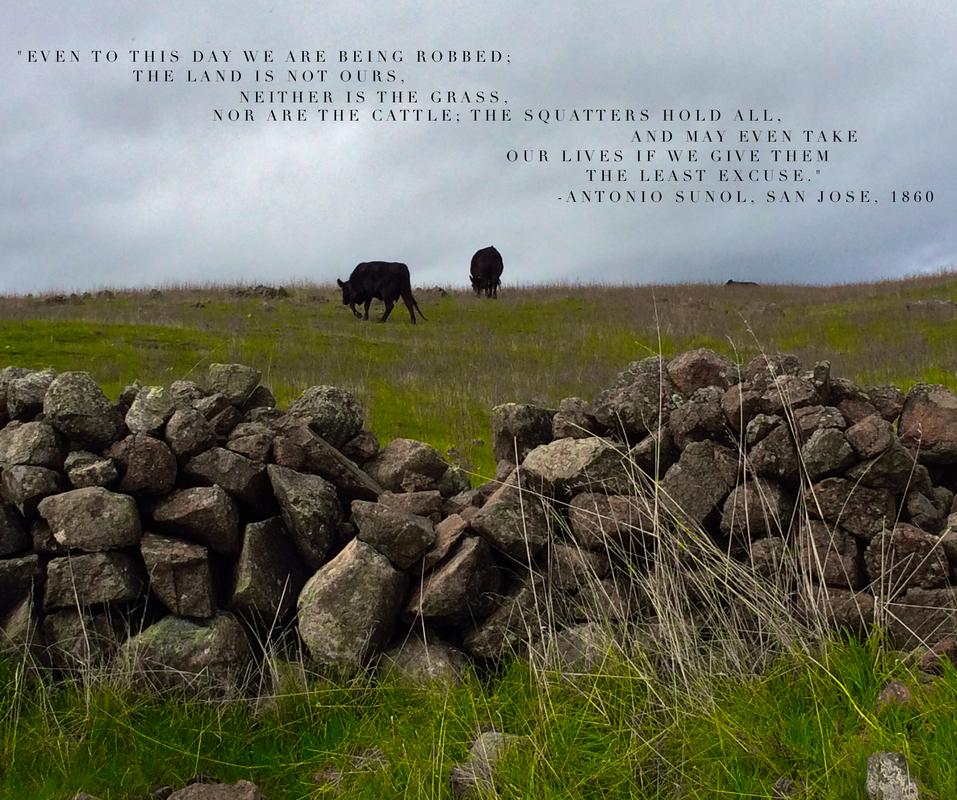

Zacarías's nephew, the younger Antonio Sunol, was killed by a squatter while patrolling the family’s rancho. The intruder had been haphazardly shooting at cattle until one dropped, wounding many, and Antonio, from his horse, had confronted him about the cruelty and waste. He had invited the shooter to come to his home and get all the meat he desired, but asked him to stop killing and wounding the cattle. In response, the squatter shot Antonio. His broken-hearted father, the senior Antonio, lost any vestiges of support he might have had for the American infiltration of California. - from MINE: El Despojo de María Zacarías Bernal de Berreyesa

2 Comments

I'm ambling around the local park, where the grass is sparkling with dandelion blooms that bring my Audrey to mind. I used to call her my "dandelion daughter" when she was little, because she was such a bright, strong-rooted girl who couldn't be repressed -- and yet could be delicate, too. Sometimes, like now, I selfishly wish she hadn't moved to Hawaii.

There's a team of girls practicing soccer in the field, just like she used to do. They're all dressed in different bold colors, making me think of a tumble of Skittles -- Audrey loved those candies. She loved playing soccer, too. I'm remembering how hard she'd run for the ball, how her face would light up and she'd follow her kick with a laugh. I've walked fifty yards farther when I see something red in the grass, the only piece of litter in sight. It's a Skittles wrapper next to a dandelion bloom -- no, I'm not making this up. And as I'm trying to put that coincidence together, the coach on the field yells "You got this, Audrey!" -- and I just have to smile and think, oh yes you do, and I'm so happy for you. Stay where you are and bloom with all your might. The universe has many voices, and sometimes it talks to me in several of them at a time. 226 years ago today, María Zacarías Bernal de Berreyesa was born in the presidio barracks of San Francisco. She almost didn't make it -- she was so near death at birth that she had to be rushed to the tiny chapel next door for an emergency baptism by the commandante. These are the ruins of the chapel where she was "saved" -- her soldier father, Joaquin Bernal, may have laid these foundational stones as one of his duties. I'm celebrating her birthday, her survival, and the completion of my book with a sangria at the Presidio Officer's Club, just a few feet away from the barracks and chapel sites. Today seems like a good day -- and this seems like the perfect place -- to begin sharing bits of her story with you. Here's a scrap from the prologue of MINE, about the night she was born and baptized, November 5, 1791: Candlelight quivers across a bloodstained bed, where a weary-eyed woman is curled on her side, watching a midwife bend over a silent bundle. A sweating young soldier stands inside the door, turning his hat in his hands. Voices drift through the glassless windows, the brief worried questions of relatives--¿esta bien? ¿Aun vive?—the murmur of women, and the whimpering of the newborn’s two sisters. I can hear the disconsolate squawks of wet chickens, the rumble of waves on the nearby shore, the rain that falls through the thatched roof and thuds on the floor. The baby has been born instantem periculum mortis, in danger of immediate death, and might not live long enough to be baptized at Mission Dolores four miles off—not even long enough to send for a priest.  This photo was taken by Mary Lovely, a lovely stranger who listened with enthusiasm as I explained while I'm here. Thanks for listening, Mary.)  It's been an educational, vertebrae-crunching six years, but MINE: El Despojo de María Zacarías Bernal de Berreyesa is now off to my hoped-for publisher and SJSU! Here's a little intro to Zacarías and her tale.

María Zacarías Bernal de Berreyesa was a Spanish-Mexican matriarch of early San José. The Bernals and Berreyesas had arrived in San Francisco in 1776, and helped settle the Bay Area throughout the mid-1800s; Zacarías’s father and husband were ranchers of neighboring estates in San José, and the hides-and-tallow trade had made them rich. But in 1846 John C. Frémont came to town, and began his destruction of Zacarías’s world. With his support (if not instigation), the Bear Flaggers revolted and captured three of her sons. When her husband rode north to check on their welfare, he was murdered by Kit Carson, acting on Frémont’s order. When the Gold Rushers swarmed in three years later, the widow’s land ownership was questioned—as were all Californio claims of land ownership. Zacarias, though, had a quicksilver mine on her land, and that metal made gold much easier to refine. Mercury rose in price, and sixty claimants rose against her—squatters, capitalists, and their lawyers. Even President Lincoln sent men to claim the mine, but she held her ground all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1863 the mine operations were decided to be on her rancho, but by the time that league of land was affirmed to be hers, it had been sold to cover legal bills. Financial losses were meaningless, though, because by then she had also lost nine of ten sons—some of them to violence and vigilante mobs, fueled by the tensions over the land and mines—seven sons gone in one turbulent decade alone. It is our overlapped places and fears that connect Zacarías and me. Rancho San Vicente, so integral to her life and livelihood, has felt like “mine” for decades. It is still open land, except for the corner where my children’s grade school stands, and I have spent countless hours along her creek, journaling my thoughts and worries. So I have told Zacarías’s tale of losses through connections of the heart, weaving our experiences together in situ to “ground” our empathy, playing out our stories on our common stage, under the influence of places and seasons we have shared across time. Like most Californians, I grew up with a fourth-grade, mission-project vision of our state’s earliest history: I remembered only bell towers, and gray-robed priests, and smallpox epidemics that had killed many Indians. I knew nothing of the Californios who had “owned” the land for seventy-plus years, of their permanent disruption by the massive influx of foreigners—whites—after 1848. Research showed me what American greed cost Zacarías and her people, but my heart showed me who she was through places and sons. I have looked at her life through the lens of our love for both. MINE is intended to resonate across cultural and political lines, to create empathy for Zacarías as a mother and woman, and to deepen awareness of our state’s Spanish-Mexican roots. Knotholes scar the broad boards of the faded fence,

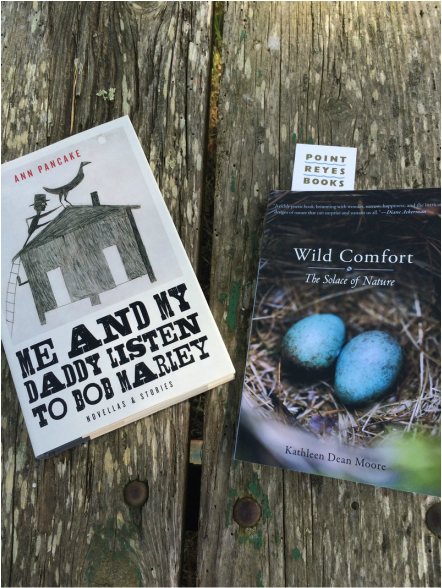

like age spots on a weathered face framed by funky hot pink bangs of bougainvilla blooms. Knotholes cheapen lumber for builders but enrich it for me. Knotholes are cross-sections of joints, Reminders of branches that used to be Buttresses for birds’ nests, Byways for squirrels, and Beds for raccoons. Knotholes record, in the grooves of their rings, The soundtracks of chipmunks, owls, wrens, ravens, and jays-- Lifetimes in squabble and song Playing silently on. Knotholes are signs of outgrowth, and so of Life-- The life of the tree, the lives of each of its denizens, The lives of we who inhaled its Invisible gifts. They signify the whole of the ever-giving tree. Knotholes are not holes but Wholeness. I awaken at five to a window-framed sky the color of a chalkboard erased. A current of the wild night sifts through the screen, leaving only the finest scent-grains of dampened pine. The stuttering howls of coyotes tear at the dark. Nearby, a bird’s cha CHEE, CHA chee repeats incessantly. In just a few hours, I will make my way back to the Geography of Hope conference in Point Reyes, where environmentalist writers have gathered this weekend to inspire and inform one another. The panelists are from the pantheon of the preservation movement: Gretel Ehrlich, Kathleen Dean Moore, Robert Hass, Ann Pancake, Rebecca Solnit, and dozens more. I have been awed by the discoveries of writing that moved me to tears. I have been inspired to write with a clearer intent to effect progressive change. I have also felt ashamed for not putting my words to more preventive, restorative, salvaging use long ago. For most of my life I have cringed and averted my eyes from damage done by humans to our fellow animals, especially through hunting and habitat destruction. Graphics and facts disturb me to the point of sickness, and leave me with the despair of unfixable violence. Yes, I have donated dollars and written occasional letters to save whales and wolves, but in general I have settled for picking up litter and shopping with care, and for aiding individual creatures in my path. What real difference have I made in the problems that trouble me most – all of which center on creatures' suffering? Have I ever believed it was enough to have adopted some dogs, saved a few trees, and helped care for some injured birds? I am 52 years old, and I have been painfully passionate about animals' demise for at least five decades now.

Where have I been all my life? My shame was deepened yesterday by the indignation of a self-proclaimed “warrior” for The Cause, a fellow attendee who declared she had found us all wanting. “I look around and feel no affinity, no connection to any of you,” she had said peremptorily, the back of her hand flipping toward us in a dismissive wave. I wanted to point out that the topic here was Hope, not War, but I knew that it was the war that had given such hope, and that there were endless battles yet to be fought. The rest of us sat quietly, absorbing her judgment, wondering where we fell short. It was the only negative remark I had heard all day, and that isolation had charged it with extra power. I get up, restless now with two kinds of inaction, and go to the window that faces the eastern hills. The sky is becoming a swath of bleached gray flannel, the tips of the pines poking through its fraying edge. A crow beats overhead in silhouette, its wings pushing down on the air like a pair of bellows. The bright cha CHEE of the pre-dawn bird has ended suddenly, as if Pan has pressed the snooze button on nature’s alarm. I can no longer hear the coyotes’ wails and barks. The earth’s creatures are changing behaviors in tune with its light, contributing to the movement and sounds of the planet according to its natural order. No words can cause the crow to soar at night, or make coyotes howl throughout the day. Or make political warriors of introverts. An army relies on its journalists, artists, medics, mechanics, cooks, and photographers, too. I rest my elbows on the windowsill. A pale peach sunrise burns between the bare lower trunks of the pines. Yesterday’s sunrise was a vibrant chorus of high-volume, oil-based art. Today shows up quietly, as a whisper of watercolor, equally beautiful, and just as much of a gift. This is an excerpt from the book I'm writing about the extraordinary life of a local Spanish-Mexican matriarch, a first generation colonist of San Jose. I wanted to share bits and pieces as I go, with the caveat that, like all works in process (and life), it's subject to change.

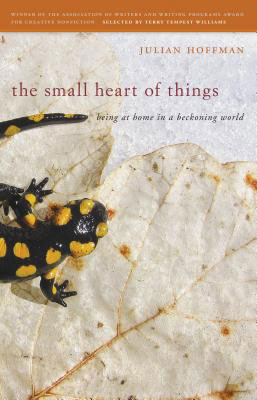

At eight o’clock in the morning, I am the only person on the trail beside Los Alamitos Creek. It is sunny and clear, with enough of a breeze to make faint songs of leaves. New light shimmers on night-moistened chaparral. The oaks are dark and lush. Sycamore branches, heavy with glossy green foliage, drape to the ground and rest there in jagged swoops, like the handkerchief hem of a gown. Their hole-punched bark and three-toed leaves lie all across the trail. Poison oak vines, pink with sun, encircle trunks. There are patches of darkness on Los Alamitos, places the sun gives only a passing glance. In summer fish linger within these mossy pools, watching for fallen mosquitos and hiding from herons. Today I, too, am drawn to shadowed places, to the bank where my boy once played in the shade of an oak. I have named this oak the Wailing Windblown Woman because, like the famous picture that can be seen as either a beauty or a hag, its shape can take two forms. Its tall trunk curves like an arcing spine, and its limbs grow laterally in one direction. I can see her as a woman facing a strong wind, her arms outstretched behind her, her hair and skirt blown back, reveling in nature’s power. Or I can see her as turned the other direction, a woman bent over in grief, her hair hanging down in her face, her arms reaching forward in supplication. Today I see her as Windblown Woman, because I am looking for strength, and the birds are singing in sweet staccato trills. In late August of 1842, on a warm day like this, Zacarias might have been doing her wash at this creek, or at least supervising the Indian servants who did – servants whose “payment” was typically room, board, and clothes. But for time I would see them all now, carrying stacks of soiled linens from the rickety carreta down to the shallow creek. A pair of yoked oxen would be snuffling and stamping at flies. The shouts of vaqueros and thudding of hooves would be drifting from the plain. There would be a picnic spread over the banks, sure to include tortillas, tomatoes, olives, figs, and beef. The air would be fragrant with food and homemade soap, along with the constant scent of hot weeds and manure. The girls and women would be standing in the creek, scrubbing the linens against the stones. Snowy white linens were the pride of every Spanish-Mexican family, and the doñas and daughters wore white except in mourning; families being large, this was all too often the case. Zacarias might be sitting on this very boulder, keeping one eye on eleven-year-old Domingo and nine-year-old Magdalena, and one eye out for intruders. Her grown daughters Loreta and Carmen, whose double wedding three years earlier had already produced three girls, might have been there with both surviving babies in arms, as might have Santiago’s pregnant wife, with their one living child, and numerous nieces and nephews and cousins as well. Today Zacarias’s older sons would be helping their father on the ranch. Reyes might not be quite himself; he had received Governor Alvarado’s confirmation of his land grant on the 20th – the prefect of Monterey had vouched for his character, recommending confirmation on the basis of “the honesty, numerous family, and good services of Señor Berryessa”– but only for one league, not two. For eight years he had been unable to claim the title to the two leagues granted him by Governor Figeuroa, who had since died; a neighbor, Justo Larios, was still contesting the boundaries. It was a frustrating situation, and one of more critical import than Reyes knew. * * * I return to the stream in the afternoon, when the sun is sliding behind the sycamores, and the gnats are rising up in languid drifts. Zacarias would be heading homeward now, the creaky carreta loaded with stacks of folded white linens, laundry supplies, and leftover picnic fare. I imagine Domingo, perhaps the only son still home all day, walking beside his middle-aged mother, holding her elbow as she steps around thistles and stones. He is the tenth boy of ten, born in 1830, six weeks before Ignacio’s wedding day. Zacarias had held her last son in her arms while her first son danced in his bride’s. An unexpected breeze disturbs the Windblown Woman. Pollen drifts down around me in clouds, sifting back and forth until it lands in the shaded creek. The water flinches. Maybe the woman is wailing after all. In mid-March I had the honor of hosting Julian Hoffman, author of The Small Heart of Things, during his book tour along the Pacific coast. Julian was visiting from the remote Prespa region of Greece, to which he and his wife had moved from London fourteen years ago – inspired by a beautiful book and a bottle of wine. There he writes essays of place, wherein stories emerge coaxed by traces of movement, odd objects found, or unexpected encounters. Each essay is a lyrical weave of observations, a detailed examination of “the small heart of things” that conveys a significant truth. Even his salaried work takes this form; he details the behavior of birds for a cause, for the big-picture planning of Grecian windmill farms. Spending time with Julian, whose writing and other work emanate from noticing, was a quiet lesson in just that– in being present and appreciating what is here right now. Strolling through the Santa Cruz redwoods I had always loved, his enthusiasm for overlooked life forms gave me pause. His pace and mindful presence brought small things into awareness, and his appreciation revealed them as the works of art they are. In doing and protecting I had nearly forgotten the reassuring perfection of nature, the order and beauty in every living thing – not just the grand. I was reminded more by Julian’s delight over banana slugs, miniscule mushrooms beneath dead leaves, and lavender lichen encrusting the end of a log than by his more tenable awe at the trees themselves. At home, in the woods, and at Julian’s readings it was clear that his genuine interest in living things extends to his fellow man – that it doubtless originates there. As he spoke with my friends and family, fellow hikers, and numerous fans, I could tell he was sharing from the same heart that once attended to a winter moth, a half-drowned salamander, and a pod of dolphins stitching across the sea. In his attentive connections I could see the source of his personal peace and the basis for his warm relationships. It is a kind of noticing that exceeds observation, an awareness that goes beyond making elaborate notes, a knowledge that paying attention is a gift to one’s self and to all; for, as the poet Rilke says, and Julian reverently quotes, “everything beckons to us to perceive it.”

I am grateful for the rich gifts of Julian’s book, time, conversation, writing advice, and kindness to my family. But it is the gift of attentiveness that has already changed “the small heart of things” for me. This is an excerpt from the book I'm writing about the extraordinary life of a local Spanish-Mexican matriarch, a first generation colonist of San Jose. I wanted to share bits and pieces as I go, with the caveat that, like all works in process (and life), it's subject to change. Fog swirls over the six-by-six excavation. A rusted metal liner surrounds some serpentinite stones, each scabbed with bronze moss and edged with tufts of weeds. The allure to archaeologists would be unclear, but for the white words stenciled inside the frame: PRESIDIO DE SAN FRANCISCO, 1780 CHAPEL, NAVE and ALTAR. This is a piece of the chapel’s foundation -- the place where a commandante once saved a little girl’s soul. Long before I had ever heard of Maria Zacarias Bernal Berreyesa, I intimately knew her rural league of land in south San Jose. The former Rancho San Vicente lies between two ranges near my home in the foothills, and my children attended school on a developed corner of the old ranch, just a stone’s throw from the creek along its border. On warm afternoons I would pick them up and take them directly to Los Alamitos to rinse away the day’s restraints, to feed ducks, build dams, and skim stones. But I would visit most often with my dog at dawn or dusk, when I heard only water, wind, and birds, and saw only creatures too cautious to come very close – though sometimes a rabbit or bobcat would dart from the shrubs. It was a place of solitude and meditation, where I was reminded that nothing is wasted or ugly or meaningless -- that new life always grows from the broken, fallen, old, and scarred. And the land was my touchstone when suburbia threatened my soul. In the twenty-four years I had been walking the two-mile loop around Los Alamitos Creek, I had noticed too many oddities not to wonder what might haunt it. The property exuded a known history through its rusted found objects and proximity to old quicksilver mines, but I was certain something else was embedded there, something deeper than mercury mine shafts and cinnabar caves, something richer than ore. I was intrigued by the stories I saw in particular places. The dark green surf of non-native vinca flooding a bank, the face of a snarling devil in the knots of an oak, a vignette of small animal skulls aligned in the mud. Places in the path where my dog refused to go, and when carried there, she trembled in my arms. The distorted scar of an arrow carved in a trunk. Crickets creaking in the middle of the day, frogs croaking at dawn, vultures hunkering together on rocks in the middle of the creek. Rusted mattress springs. Rotted chunks of lumber, bits of tumbled brick, a metal cart beneath the gritty silt. Thick paddles of cactus poking through patches of weeds. Unlikely pedestrians had also piqued my interest over the years. I repeatedly encountered people who did not conform to the standard suburban scene: A muttering woman with long silver hair wearing gypsy skirts and Keds, perpetually walking local streets and trails – a woman I had seen in my childhood, too, incessantly tracing another county’s veins . A hulking, sixty-something man preceded by five loose Chihuahuas; he introduced himself as a native Czech jazzman who ice skates at sunrise each day at the local rink. And then there was Ray, a convivial, middle-aged man whose grin, ponytail, and John Lennon glasses made him seem forever (and happily) stuck in the Summer of Love. The collective, recurring nature of these anomalies had always implied mystery along the creek, an impression of something significant under its skin. It was like being in an empty gothic chapel, where all is in perfect order and exudes simplistic grace, yet one senses hidden things wedged in the vaults, invisible stains seeping in through the fretwork. The beauty and peace of the place might still provide comfort -- but the aberration nonetheless exists, residual baseness permeating art. One fortunate day, Mary Berger and Heidi McFarland of the Almaden Quicksilver Mining Museum put a name to that sense. It did not surprise me to learn that the land that had been so meaningful to me had been of enormous significance to another woman – in fact, to the nation. But what Mary and Heidi told me about her life prickled my skin and touched my heart. What I learned from her great-nephew, San Jose's official historian and Superior Court judge Paul Bernal, sparked my quest. Together, their words began a journey that has led me here today, searching for Maria Zacarias.

Thank you for reading this excerpt from MINE -- your comments are always welcome! If you'd like to know when I post another, please subscribe for updates. The wild pigs are back this dry winter day, snuffling about in the dead leaves on my neighbor’s front lawn. I pull up beside them and lean on the horn, trying to scare them off to their homeland hills. Despite the months they spent last summer overturning my own yard, I sincerely want to save their smelly skins. If the manager of the golf course gets wind (so to speak) of their return, the pigs will be trapped and shot. My home is at the wild rim of theirs, positioned between two extremes: Almaden Quicksilver County Park and the Almaden Country Club. On one side a natural wilderness open to all; on the other, a manicured golf course open to members. The pigs have no interest in membership, nor in trespassing over (and under) the precious turf – not in normal weather, anyway. But it’s been an extremely dry year, and the pond across the street, at the edge of the course, has lured them out of bounds. The pond is really a club-owned reservoir for water traps, but over the decades its has become a home for herons, hawks, and ducks, and a wayside inn for cougars, coyotes, and deer -- not pigs, however. Last summer the country club, looking for a valve, drained most of the water away. The pond fell to one-fourth its original depth, leaving concentric shorelines of muck and stench. It’s not hard to imagine what happened next. One day in July, when a rare wind blew this inviting scent their way, a large herd of boar in the hills stopped their grunting and rooting. They wiggled their dusty snouts in the air, then glanced at each other and grinned with porcine joy. Abandoning the hard-packed ground, the half-dozen adults summoned their two dozen piglets, then jostled and tumbled their way toward the feast below. They arrived at my yard first, and, quite pleased with the array of heavy appetizers offered there, lingered for weeks, enjoying the ease with which they could flip over the flagstones I reset each day, and root under the nursery perennials I kept replanting. I’m sure they thought I was simply replenishing the buffet. When I chased them off, they retreated a few yards into the park, where they basked in the dust until I went back in the house. Just give her a minute, I could hear them muttering to each other. After a while they wouldn’t retreat at all. Once I leaned over the deck railing eighteen inches over their heads, threw pebbles, clapped, and yelled Scram! Two 300-pound sows looked up, gave a snort, and flicked their bristly hides. Obviously terrified by my harsh language and dangerous projectiles, they lay down and wallowed on their backs, sticking their muddy cloven hooves in the air, right beneath my highly offended nose. The piglets cavorted around their moms in glee. I gave up. They clearly sensed I didn’t have it in me to do any more violence than that. Besides, I knew they’d leave, as they had in other years, when the rains came and softened their home grounds. But the rains didn’t come. When the pigs had extracted and gobbled every earthworm and grub, they followed their snouts past my house and across the street, to the increasingly odiferous pond. There they rolled and feasted in rich yards of exposed shoreline mud, generously seasoned by years of layers of waterfowl manure. Between gorgings they lolled about in the sun, bellies bloated, on slopes. One day one of them climbed high enough to spot a glimpse of the golf course through the oaks, just across the street on the far side of the pond. Scarcely believing their unending good fortune, they lumbered to their feet, waddled happily onto the unfenced course, and began to enjoy the dessert bar beneath Hole Three. This course on the course lasted several weeks while the country club tried mending and chasing, as I had, and with equal effectiveness. Occasionally the herd would trundle back to the pond for spa treatments in the mud, crossing the street properly and legally at the stop sign. Traffic would back up while three dozen sows and piglets trotted past in single file, all variously adorned in solids, stripes, and spots, wearing dirty snouts and expressions of satiated bliss. For the pigs it was a summer of decadence; for homeowners and golf course managers, an oddly charming but very expensive mess. Homeowners responded, for the most part, just as I had -- enjoying and allowing nature to happen while whining about the destruction and cost. But the country club, claiming they had tried everything else possible, obtained an “emergency permit” to kill the very guests they had invited by draining the reservoir pond. The pigs had no Mulligans left. One morning while I was out of town, my neighbors heard ten gunshots at the pond -- a family caught in a trap and killed one by one. After that, the rest of the pigs vanished into the hills. So when I see the pigs again three months later, only one street away from the course, I fear for their hides. The temporary hunting permit has expired, but I know it can all too easily be renewed. I honk and yell – as usual, to no avail. I have to laugh at myself for repeating the same ineffective measures, and at them, too, just for being so cocky and comical-looking. But then I look closer, and my grin fades. The mien of these feral pigs is much different now. The sass of their former frolicking is gone. They’re sluggishly lifting their heavy heads to gaze wearily at me with deeply sunken eyes, three tired old sows surrounded by a few piglets frantically grabbing at teats. These piglets are new, the litter smaller because of the lack of food. One of them might be the piglet whose frantic squeals awakened me at two o'clock this morning; Leaping up and looking out the window, I saw two coyotes batting it back and forth across the moonlit lawn. I scared them off, but I felt bad for the hungry canines, too -- all wild things are undernourished now. It’s clear this excursion into suburbia is not the optional feast of last summer and fall. The continuing drought has made the pigs desperate, driving them over their boundaries again to survive. One sow takes a half-step toward me, plants her hooves squarely, and looks me straight in the eye through my car window. She stands for a moment, not chewing, not flicking her tail, not moving at all -- just staring. Her eyes are dull. We don’t have a choice, she seems to say. Just look at all these kids! And then, wheeling ponderously away, she returns to half-heartedly snuffling through layers of leaves. A piglet scrambles after her, tugging at a teat that has probably gone dry.

I’m pleased to add that it has finally rained since I wrote this post a few days ago, and the wild pigs have disappeared into the hills again -- safe, for the moment. |

Welcome to

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed