|

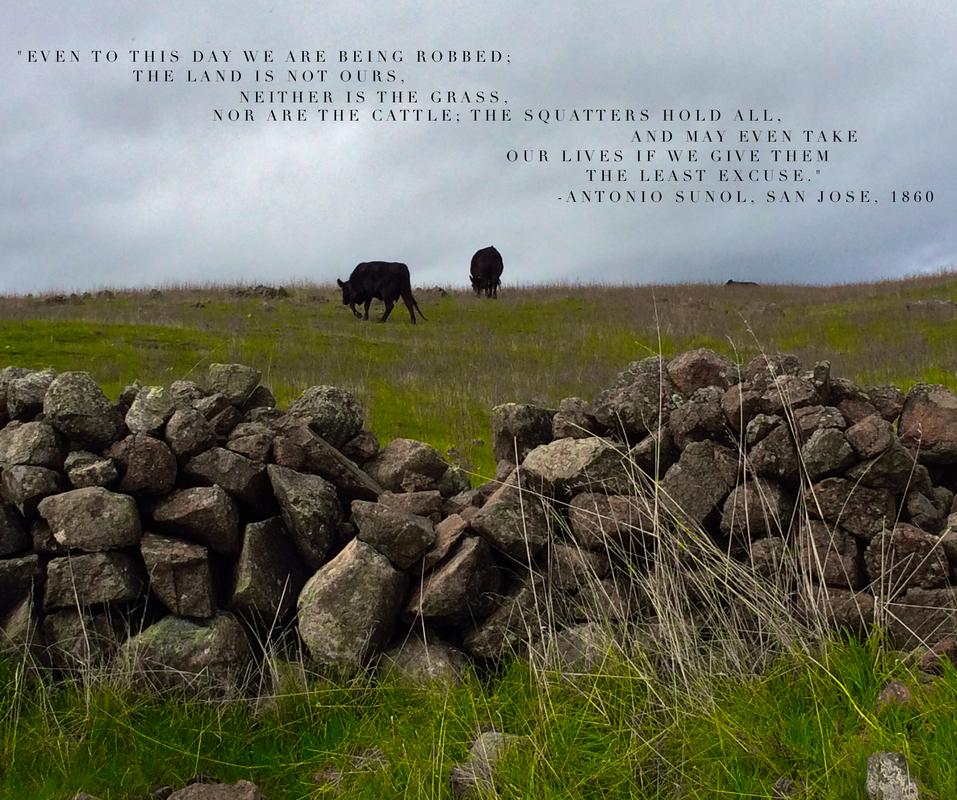

Zacarías's nephew, the younger Antonio Sunol, was killed by a squatter while patrolling the family’s rancho. The intruder had been haphazardly shooting at cattle until one dropped, wounding many, and Antonio, from his horse, had confronted him about the cruelty and waste. He had invited the shooter to come to his home and get all the meat he desired, but asked him to stop killing and wounding the cattle. In response, the squatter shot Antonio. His broken-hearted father, the senior Antonio, lost any vestiges of support he might have had for the American infiltration of California. - from MINE: El Despojo de María Zacarías Bernal de Berreyesa

2 Comments

I'm ambling around the local park, where the grass is sparkling with dandelion blooms that bring my Audrey to mind. I used to call her my "dandelion daughter" when she was little, because she was such a bright, strong-rooted girl who couldn't be repressed -- and yet could be delicate, too. Sometimes, like now, I selfishly wish she hadn't moved to Hawaii.

There's a team of girls practicing soccer in the field, just like she used to do. They're all dressed in different bold colors, making me think of a tumble of Skittles -- Audrey loved those candies. She loved playing soccer, too. I'm remembering how hard she'd run for the ball, how her face would light up and she'd follow her kick with a laugh. I've walked fifty yards farther when I see something red in the grass, the only piece of litter in sight. It's a Skittles wrapper next to a dandelion bloom -- no, I'm not making this up. And as I'm trying to put that coincidence together, the coach on the field yells "You got this, Audrey!" -- and I just have to smile and think, oh yes you do, and I'm so happy for you. Stay where you are and bloom with all your might. The universe has many voices, and sometimes it talks to me in several of them at a time. 226 years ago today, María Zacarías Bernal de Berreyesa was born in the presidio barracks of San Francisco. She almost didn't make it -- she was so near death at birth that she had to be rushed to the tiny chapel next door for an emergency baptism by the commandante. These are the ruins of the chapel where she was "saved" -- her soldier father, Joaquin Bernal, may have laid these foundational stones as one of his duties. I'm celebrating her birthday, her survival, and the completion of my book with a sangria at the Presidio Officer's Club, just a few feet away from the barracks and chapel sites. Today seems like a good day -- and this seems like the perfect place -- to begin sharing bits of her story with you. Here's a scrap from the prologue of MINE, about the night she was born and baptized, November 5, 1791: Candlelight quivers across a bloodstained bed, where a weary-eyed woman is curled on her side, watching a midwife bend over a silent bundle. A sweating young soldier stands inside the door, turning his hat in his hands. Voices drift through the glassless windows, the brief worried questions of relatives--¿esta bien? ¿Aun vive?—the murmur of women, and the whimpering of the newborn’s two sisters. I can hear the disconsolate squawks of wet chickens, the rumble of waves on the nearby shore, the rain that falls through the thatched roof and thuds on the floor. The baby has been born instantem periculum mortis, in danger of immediate death, and might not live long enough to be baptized at Mission Dolores four miles off—not even long enough to send for a priest.  This photo was taken by Mary Lovely, a lovely stranger who listened with enthusiasm as I explained while I'm here. Thanks for listening, Mary.)  It's been an educational, vertebrae-crunching six years, but MINE: El Despojo de María Zacarías Bernal de Berreyesa is now off to my hoped-for publisher and SJSU! Here's a little intro to Zacarías and her tale.

María Zacarías Bernal de Berreyesa was a Spanish-Mexican matriarch of early San José. The Bernals and Berreyesas had arrived in San Francisco in 1776, and helped settle the Bay Area throughout the mid-1800s; Zacarías’s father and husband were ranchers of neighboring estates in San José, and the hides-and-tallow trade had made them rich. But in 1846 John C. Frémont came to town, and began his destruction of Zacarías’s world. With his support (if not instigation), the Bear Flaggers revolted and captured three of her sons. When her husband rode north to check on their welfare, he was murdered by Kit Carson, acting on Frémont’s order. When the Gold Rushers swarmed in three years later, the widow’s land ownership was questioned—as were all Californio claims of land ownership. Zacarias, though, had a quicksilver mine on her land, and that metal made gold much easier to refine. Mercury rose in price, and sixty claimants rose against her—squatters, capitalists, and their lawyers. Even President Lincoln sent men to claim the mine, but she held her ground all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1863 the mine operations were decided to be on her rancho, but by the time that league of land was affirmed to be hers, it had been sold to cover legal bills. Financial losses were meaningless, though, because by then she had also lost nine of ten sons—some of them to violence and vigilante mobs, fueled by the tensions over the land and mines—seven sons gone in one turbulent decade alone. It is our overlapped places and fears that connect Zacarías and me. Rancho San Vicente, so integral to her life and livelihood, has felt like “mine” for decades. It is still open land, except for the corner where my children’s grade school stands, and I have spent countless hours along her creek, journaling my thoughts and worries. So I have told Zacarías’s tale of losses through connections of the heart, weaving our experiences together in situ to “ground” our empathy, playing out our stories on our common stage, under the influence of places and seasons we have shared across time. Like most Californians, I grew up with a fourth-grade, mission-project vision of our state’s earliest history: I remembered only bell towers, and gray-robed priests, and smallpox epidemics that had killed many Indians. I knew nothing of the Californios who had “owned” the land for seventy-plus years, of their permanent disruption by the massive influx of foreigners—whites—after 1848. Research showed me what American greed cost Zacarías and her people, but my heart showed me who she was through places and sons. I have looked at her life through the lens of our love for both. MINE is intended to resonate across cultural and political lines, to create empathy for Zacarías as a mother and woman, and to deepen awareness of our state’s Spanish-Mexican roots. |

Welcome to

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed