|

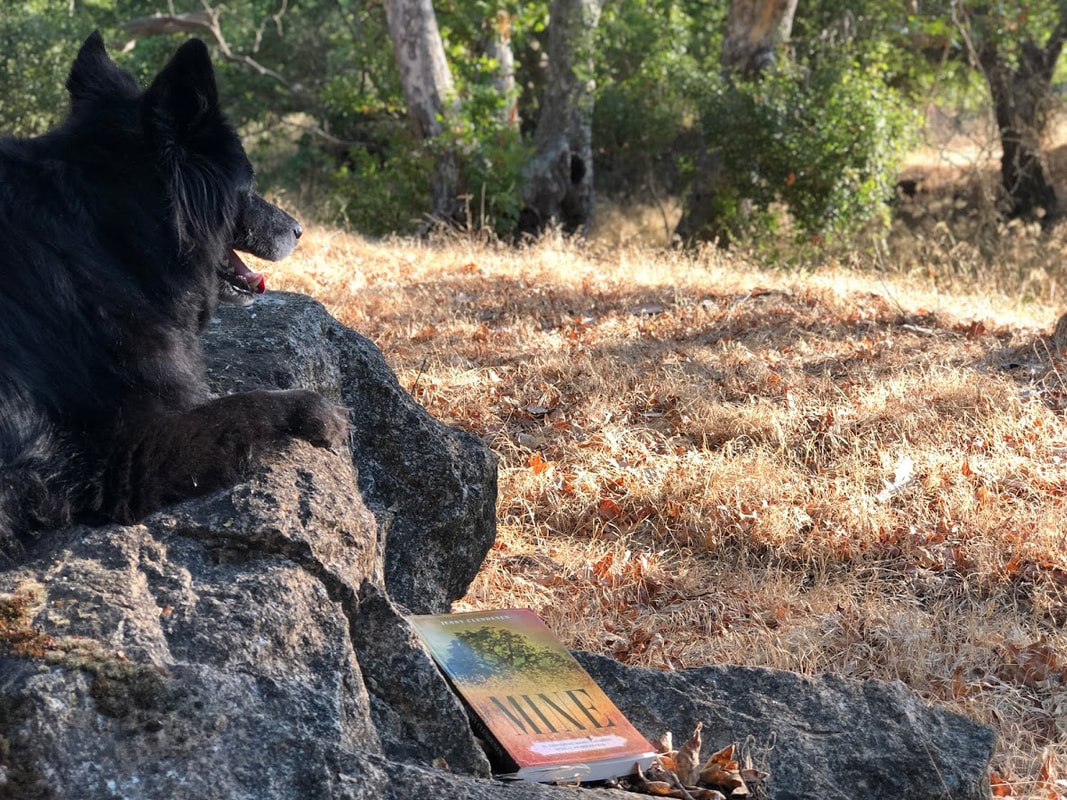

On Sunday I carried sweet Darcy to the banks of Los Alamitos Creek, where we’d walked together for over a dozen years, and had shared experiences of the heart that had led to my book. An editor needed a photo for an upcoming review, and I wanted to place her in situ one more time. She couldn’t walk, at sixteen, with spinal arthritis, but her attitude was happy, as always, and she posed patiently. I didn’t know she was one day away from death. I had chosen a place on the creek where I wouldn’t have to carry her very far, and where the foxtails wouldn’t be too thick, and the bank too steep. When we reached the shore I looked up and realized I had brought her to the very place I’d come to grieve in mid-July of 2003, right after my dad died, a memory I’d included in the book as a connection to Maria Zacarias, who once lived there. I believed she, too, must have come to that place to grieve her own father’s death. So the place was layered already with then and now, with loss and memory, with pages in process and the published book now in my hand. My dear dog was my shadow in that story, as in everything else. And once again it was a poignant evening of weed-gilding light, giving me an elevated view of summer’s take on the land. It was in that heart-full, achey appreciation of what was gone that I carried my sweet girl back to the car, parked in a cul-de-sac. As I carefully placed her in the back seat and picked the burrs from her satin-smooth coat, talking to her all the while as I always have, an elderly man called out to me from behind a patio wall. “You are being so kind,” he said. His wife joined in. “We can see that you're so very kind to your dog. Kindness matters so much, doesn’t it? We had an old dog whose hind end gave out too. Thank you for being so kind.” I teared up and thanked them for their kind words, and we talked for a bit about our dear dogs, and kindness in the Days of Covid; I put on my mask so they could show me their garden sign about the importance of kindness, and I told them about having “Be brave and be kind” tattooed on my back last year, at a time when I especially needed reminding. Then I gave them my book, which I’d brought for the photo shoot, and I drove off with Gretchen’s and Greg’s words warming my heart. The drive to Watsonville through old Almaden Valley was loaded, because midsummer on that road reeked of death to me already. I had driven that back road from Almaden one June to visit my dying dad, and the next July, I returned that way from my friend’s dad’s service. I had written about that sensory drive in MINE, imagining Zacarias soaking up the same scents and sounds in the July days right after her husband’s murder, and in a later July when two of her sons were lynched. It was a drive rich with memories of mourning and learning and journaling across this land, and of being with Darcy every step, mile, and word of the way. My dear dog is written on its landscape and in its chapters. The land was astoundingly beautiful in its demise, with sunset reappearing at every curve and change in the mountains’ height--I got to see the day end several times. Once, when the sun sat over the hills behind a golden vale, I stopped at a turnout and picked up Darcy, who could no longer sit up and look out the window, so she too could see its beauty--I didn’t want to see that much gorgeousness alone. But now I’m glad I did that for her sake, that she saw her last sunset from my arms, out in the country we loved and wrote about. It was a gift from the Universe, which knew what was to come. Many more kindnesses awaited us at home. I don’t want to write about—because I can’t bear to relive--her sudden turn for the worse, or the medical reasons, or the anguish of watching her hurt. I only want to dwell on the kindness of people who came to our aid at every heartbreaking turn. The bearded Vietnam vet and ex-rancher, an acquaintance from the park, whose hopeful, cheerful greeting turned sad and deeply sympathetic when he saw her. The hand-holding couple who saw I was using a harness to lift her up, and who cheerily called out “Peace to you for doing that! We used one of those for our old dog too, and we know it’s hard. Namaste!” The woman next to me in the ER parking lot, who sensed my sorrow while I was waiting for Darcy outside, and let me love on her own aging Border Collie mix. The trucker who, having heard the Chevron market clerk decline my request that she stay open one more minute so I could buy water for my dog, motioned me over to to his big rig, pulled open the giant sliding door, sliced open a shrink-wrapped case of water, and handed me a bottle, refusing money—“I have dogs too,” he said, not even knowing how important the timing of that one drink was. The handful of friends I told who said just the right thing, my landlord’s kind words of genuine empathy, my sister Becky getting up early to dig the grave at the family farm, my brother Dan taking the day off from work to help his adoring fur-friend out of this painful world, the vet who came to the farm on short notice to give her relief, and then peace. People who filled my heart and eyes at every turn, who sent Darcy messages of kindness I know she heard. Every dog lover’s dog is the best dog ever; Darcy was no different, except, of course, to me. But she was unusually intuitive, loyal, ever-patient, observant, and vigilant; a herd dog whose greatest goal was to keep an eye on her dwindling flock. She was unwaveringly devoted to me and the people I love. She went along with my every need—getting up at 4AM to walk under the stars, driving 14 hours to see the eclipse, waiting patiently under many a restaurant table. I never left her home alone for more than four hours, but she would lie at the window watching for me the entire time. She was so devoted to Tyler and Audrey that after they left for college, she lay by the front door for months, eyes fixed and ears pricked, listening for their return. Long after they moved to other states, even as recently as last week, she eagerly pulled me toward people who looked like them. Darcy never forgot a face or an experience; she learned everything with one try, from housebreaking to the hazards of chasing coyotes or snapping at rattlesnakes. She wasn't just smart; she was deeply intuitive and wise. Darcy assessed all kinds of situations with wisdom and accuracy. She was my radar, my barometer, my compass. I trusted her intuition even more than mine. She put her head on the laps of those she could tell were sad; in class, she chose to lie by the quietly anxious student. She knew which tense dogs to avoid and which ones she could calm. She once barked at me to “come,” then lay across a carpet cleaner’s feet, two times, barking insistently, her Batman-ears up and her eyes fixed brightly on me, to predict the massive coronary he would have before he got out of the driveway. Darcy really was the best dog ever. I will never be without my sweet girl. She was with me through the best and worst times of my life, and I was with her through hers. That didn’t stop when she breathed her last, and it won’t stop when I breathe mine.

19 Comments

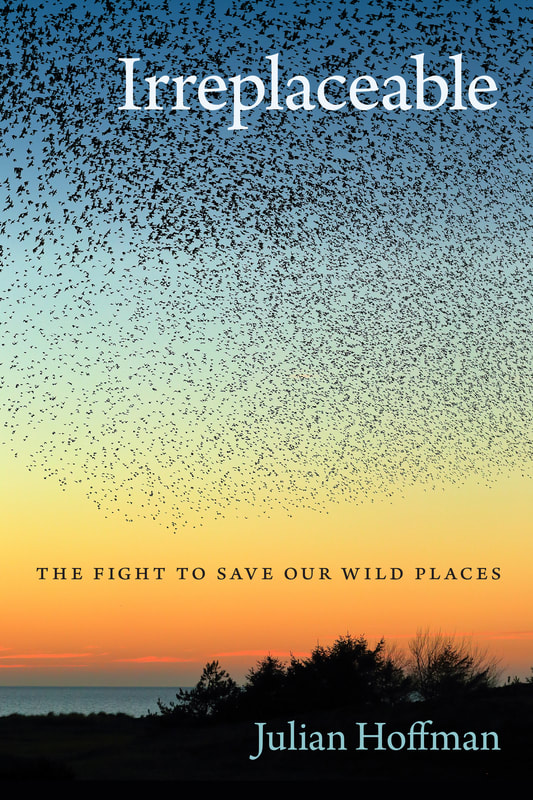

If I were to plot my watershed moments on a graph of my life, and draw lines from point to point, the result would not seem to show progress. The inner lessons learned would not plot out like formal accomplishments would: there would be very few straight strokes, and no clear pattern of upward or even forward momentum. Most of the graph would be a scribble of overlapping swoops, back and forth and up and down and around. Frankly, my growth chart would look like a loopy mess. But the longer I live, the less chaos I see in the tangle. Standing back, days or decades later, I see where seemingly small, unconnected events--a chat with a driver, the gift of a ring, a misdirected email or text--ended up criss-crossing in zig-zaggy, who'd-have-guessed ways. I see astoundingly meaningful patterns, unbound by our notion of time, unlimited by any linear sense of order. I see the proof that what goes around comes around, yet never in one perfect circle. The swirl of synchronicities that says every little thing matters. This swirling mass of small "insignificant" things forming astounding patterns is an opening image in my friend Julian Hoffman's new book, Irreplaceable. He's describing a murmuration of starlings from underneath a pier, a rise of a thousand-plus birds into a shape-shifting form: "The starlings spiralled, ribboned and wavered, a vast tremulous cloud of intelligence, each curvature and warp in the air a response to their dynamic but precise volatility"--and a stunning show of collaboration and beauty. But the birds aren't performing for humans; none of them is trying to astound. As Julian says: Each and every starling in the shifting body of birds is constantly moving in relation to its closest companions, regardless of the flock's size. According to an Italian study, orientation and velocity are precisely calibrated to a starling's seven nearest neighbours, so that the orchestral swing of a murmuration is governed by tiny deviations almost instantaneously transmitted by way of a ripple effect through the entire assembly. The first time I read this scene I was at the beach in Santa Cruz, where ripple effects were at my feet in glittery residue of rocks, and in surging waves from faraway continents. It brought to mind my belief in the connectedness of all things, not only spiritually but elementally, not only laterally but deeply through eons. We are all acting in concert with our neighbors, intentionally or not; every action has repercussive effects. And as that thought arose, so did a murmuration, right in front of me, out of a half-sunken ship. Awed by the synchrony, I thought of the swirls that my friendship with Julian had created. We had first connected in 2011, when he responded warmly to my comment on his gorgeous, prize-winning essay on Terrain.org--I quickly learned that's who he is, gracious and thoughtful and kind to everyone. Two years later our paths crossed in person at the AWP conference in Seattle, which had awarded his new book The Small Heart of Things their coveted nonfiction award. And the year after that, I had the honor of hosting him during his Bay Area book tour, and of introducing him to the California redwoods and elephant seals.

Three connecting loops in three years--three memorable days in 2014 that got me wondering who and what I needed to be. Three days that lit a fire under me, as a writer, an MFA student, an environmentalist, and so much more, as I wrote about here. Julian's brief visit changed the shape of my life across the next six years, from inspiration to action. The new shape was dynamic, shifting from one role or goal into another, transforming through myriad small deviations, as in Julian's description of the murmuration's flow: Together they shape-shifted into mystifying forms as evening fell around us--the black coil of a sinuous snake at sea, a bowl set spinning through salt air, a wine glass brimming with the last of the drained light. No sooner had a shape been perceived than it had already morphed into something radically unrelated, as if a sequence of ethereal phantoms, fugitive and fantastic in their unfolding. In 2019, my year of not-so-tiny deviations, Julian released Irreplaceable: The Fight to Save Our Wild Places, honoring the efforts of devoted individuals to protect certain at-risk land. His much-lauded, lyrical writing brings to light their network effect on the world, the interconnectedness of all species, the nonlinear consequences of our actions. His timely book makes it clear that everything we do, as individuals and as a species, matters, and our actions have repercussive effects in all directions, Those effects may not chart out right away; we might feel like we're on our own and going nowhere for a while. But if we do our own small part in the moment, without worrying about "measurable success" or immediate outcomes, it will all add up. This truth pervades all arenas, from external activism to personal choices. When we do what we must to be who we are, we contribute to a greater whole. And when we step back someday, we'll see a meaningful murmuration of collaboration, beauty, and progress. To purchase Irreplaceable, please consider supporting your local independent bookshop. It's also available on Amazon in hardback and paperback. I'm ambling around the local park, where the grass is sparkling with dandelion blooms that bring my Audrey to mind. I used to call her my "dandelion daughter" when she was little, because she was such a bright, strong-rooted girl who couldn't be repressed -- and yet could be delicate, too. Sometimes, like now, I selfishly wish she hadn't moved to Hawaii.

There's a team of girls practicing soccer in the field, just like she used to do. They're all dressed in different bold colors, making me think of a tumble of Skittles -- Audrey loved those candies. She loved playing soccer, too. I'm remembering how hard she'd run for the ball, how her face would light up and she'd follow her kick with a laugh. I've walked fifty yards farther when I see something red in the grass, the only piece of litter in sight. It's a Skittles wrapper next to a dandelion bloom -- no, I'm not making this up. And as I'm trying to put that coincidence together, the coach on the field yells "You got this, Audrey!" -- and I just have to smile and think, oh yes you do, and I'm so happy for you. Stay where you are and bloom with all your might. The universe has many voices, and sometimes it talks to me in several of them at a time. I awaken at five to a window-framed sky the color of a chalkboard erased. A current of the wild night sifts through the screen, leaving only the finest scent-grains of dampened pine. The stuttering howls of coyotes tear at the dark. Nearby, a bird’s cha CHEE, CHA chee repeats incessantly. In just a few hours, I will make my way back to the Geography of Hope conference in Point Reyes, where environmentalist writers have gathered this weekend to inspire and inform one another. The panelists are from the pantheon of the preservation movement: Gretel Ehrlich, Kathleen Dean Moore, Robert Hass, Ann Pancake, Rebecca Solnit, and dozens more. I have been awed by the discoveries of writing that moved me to tears. I have been inspired to write with a clearer intent to effect progressive change. I have also felt ashamed for not putting my words to more preventive, restorative, salvaging use long ago. For most of my life I have cringed and averted my eyes from damage done by humans to our fellow animals, especially through hunting and habitat destruction. Graphics and facts disturb me to the point of sickness, and leave me with the despair of unfixable violence. Yes, I have donated dollars and written occasional letters to save whales and wolves, but in general I have settled for picking up litter and shopping with care, and for aiding individual creatures in my path. What real difference have I made in the problems that trouble me most – all of which center on creatures' suffering? Have I ever believed it was enough to have adopted some dogs, saved a few trees, and helped care for some injured birds? I am 52 years old, and I have been painfully passionate about animals' demise for at least five decades now.

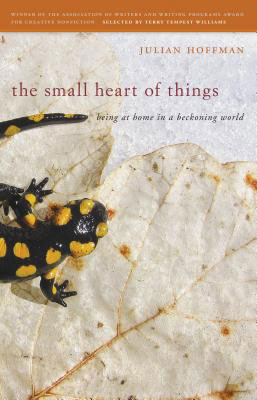

Where have I been all my life? My shame was deepened yesterday by the indignation of a self-proclaimed “warrior” for The Cause, a fellow attendee who declared she had found us all wanting. “I look around and feel no affinity, no connection to any of you,” she had said peremptorily, the back of her hand flipping toward us in a dismissive wave. I wanted to point out that the topic here was Hope, not War, but I knew that it was the war that had given such hope, and that there were endless battles yet to be fought. The rest of us sat quietly, absorbing her judgment, wondering where we fell short. It was the only negative remark I had heard all day, and that isolation had charged it with extra power. I get up, restless now with two kinds of inaction, and go to the window that faces the eastern hills. The sky is becoming a swath of bleached gray flannel, the tips of the pines poking through its fraying edge. A crow beats overhead in silhouette, its wings pushing down on the air like a pair of bellows. The bright cha CHEE of the pre-dawn bird has ended suddenly, as if Pan has pressed the snooze button on nature’s alarm. I can no longer hear the coyotes’ wails and barks. The earth’s creatures are changing behaviors in tune with its light, contributing to the movement and sounds of the planet according to its natural order. No words can cause the crow to soar at night, or make coyotes howl throughout the day. Or make political warriors of introverts. An army relies on its journalists, artists, medics, mechanics, cooks, and photographers, too. I rest my elbows on the windowsill. A pale peach sunrise burns between the bare lower trunks of the pines. Yesterday’s sunrise was a vibrant chorus of high-volume, oil-based art. Today shows up quietly, as a whisper of watercolor, equally beautiful, and just as much of a gift. In mid-March I had the honor of hosting Julian Hoffman, author of The Small Heart of Things, during his book tour along the Pacific coast. Julian was visiting from the remote Prespa region of Greece, to which he and his wife had moved from London fourteen years ago – inspired by a beautiful book and a bottle of wine. There he writes essays of place, wherein stories emerge coaxed by traces of movement, odd objects found, or unexpected encounters. Each essay is a lyrical weave of observations, a detailed examination of “the small heart of things” that conveys a significant truth. Even his salaried work takes this form; he details the behavior of birds for a cause, for the big-picture planning of Grecian windmill farms. Spending time with Julian, whose writing and other work emanate from noticing, was a quiet lesson in just that– in being present and appreciating what is here right now. Strolling through the Santa Cruz redwoods I had always loved, his enthusiasm for overlooked life forms gave me pause. His pace and mindful presence brought small things into awareness, and his appreciation revealed them as the works of art they are. In doing and protecting I had nearly forgotten the reassuring perfection of nature, the order and beauty in every living thing – not just the grand. I was reminded more by Julian’s delight over banana slugs, miniscule mushrooms beneath dead leaves, and lavender lichen encrusting the end of a log than by his more tenable awe at the trees themselves. At home, in the woods, and at Julian’s readings it was clear that his genuine interest in living things extends to his fellow man – that it doubtless originates there. As he spoke with my friends and family, fellow hikers, and numerous fans, I could tell he was sharing from the same heart that once attended to a winter moth, a half-drowned salamander, and a pod of dolphins stitching across the sea. In his attentive connections I could see the source of his personal peace and the basis for his warm relationships. It is a kind of noticing that exceeds observation, an awareness that goes beyond making elaborate notes, a knowledge that paying attention is a gift to one’s self and to all; for, as the poet Rilke says, and Julian reverently quotes, “everything beckons to us to perceive it.”

I am grateful for the rich gifts of Julian’s book, time, conversation, writing advice, and kindness to my family. But it is the gift of attentiveness that has already changed “the small heart of things” for me. |

Welcome to

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed