|

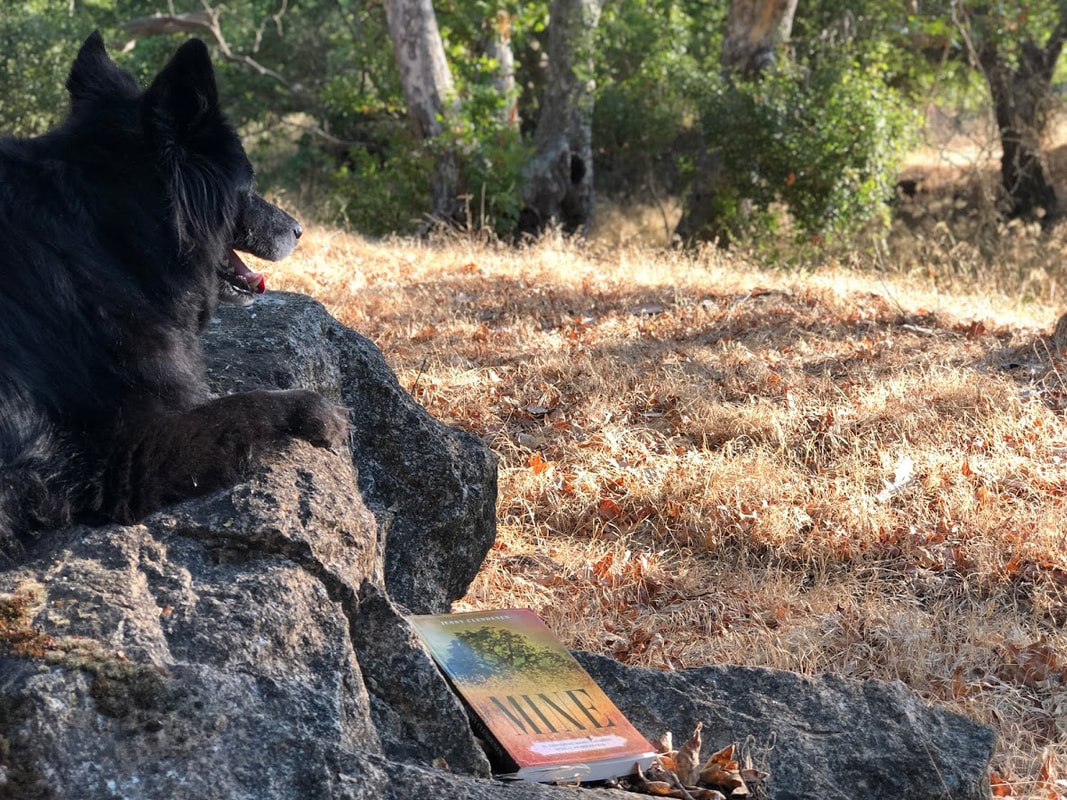

On Sunday I carried sweet Darcy to the banks of Los Alamitos Creek, where we’d walked together for over a dozen years, and had shared experiences of the heart that had led to my book. An editor needed a photo for an upcoming review, and I wanted to place her in situ one more time. She couldn’t walk, at sixteen, with spinal arthritis, but her attitude was happy, as always, and she posed patiently. I didn’t know she was one day away from death. I had chosen a place on the creek where I wouldn’t have to carry her very far, and where the foxtails wouldn’t be too thick, and the bank too steep. When we reached the shore I looked up and realized I had brought her to the very place I’d come to grieve in mid-July of 2003, right after my dad died, a memory I’d included in the book as a connection to Maria Zacarias, who once lived there. I believed she, too, must have come to that place to grieve her own father’s death. So the place was layered already with then and now, with loss and memory, with pages in process and the published book now in my hand. My dear dog was my shadow in that story, as in everything else. And once again it was a poignant evening of weed-gilding light, giving me an elevated view of summer’s take on the land. It was in that heart-full, achey appreciation of what was gone that I carried my sweet girl back to the car, parked in a cul-de-sac. As I carefully placed her in the back seat and picked the burrs from her satin-smooth coat, talking to her all the while as I always have, an elderly man called out to me from behind a patio wall. “You are being so kind,” he said. His wife joined in. “We can see that you're so very kind to your dog. Kindness matters so much, doesn’t it? We had an old dog whose hind end gave out too. Thank you for being so kind.” I teared up and thanked them for their kind words, and we talked for a bit about our dear dogs, and kindness in the Days of Covid; I put on my mask so they could show me their garden sign about the importance of kindness, and I told them about having “Be brave and be kind” tattooed on my back last year, at a time when I especially needed reminding. Then I gave them my book, which I’d brought for the photo shoot, and I drove off with Gretchen’s and Greg’s words warming my heart. The drive to Watsonville through old Almaden Valley was loaded, because midsummer on that road reeked of death to me already. I had driven that back road from Almaden one June to visit my dying dad, and the next July, I returned that way from my friend’s dad’s service. I had written about that sensory drive in MINE, imagining Zacarias soaking up the same scents and sounds in the July days right after her husband’s murder, and in a later July when two of her sons were lynched. It was a drive rich with memories of mourning and learning and journaling across this land, and of being with Darcy every step, mile, and word of the way. My dear dog is written on its landscape and in its chapters. The land was astoundingly beautiful in its demise, with sunset reappearing at every curve and change in the mountains’ height--I got to see the day end several times. Once, when the sun sat over the hills behind a golden vale, I stopped at a turnout and picked up Darcy, who could no longer sit up and look out the window, so she too could see its beauty--I didn’t want to see that much gorgeousness alone. But now I’m glad I did that for her sake, that she saw her last sunset from my arms, out in the country we loved and wrote about. It was a gift from the Universe, which knew what was to come. Many more kindnesses awaited us at home. I don’t want to write about—because I can’t bear to relive--her sudden turn for the worse, or the medical reasons, or the anguish of watching her hurt. I only want to dwell on the kindness of people who came to our aid at every heartbreaking turn. The bearded Vietnam vet and ex-rancher, an acquaintance from the park, whose hopeful, cheerful greeting turned sad and deeply sympathetic when he saw her. The hand-holding couple who saw I was using a harness to lift her up, and who cheerily called out “Peace to you for doing that! We used one of those for our old dog too, and we know it’s hard. Namaste!” The woman next to me in the ER parking lot, who sensed my sorrow while I was waiting for Darcy outside, and let me love on her own aging Border Collie mix. The trucker who, having heard the Chevron market clerk decline my request that she stay open one more minute so I could buy water for my dog, motioned me over to to his big rig, pulled open the giant sliding door, sliced open a shrink-wrapped case of water, and handed me a bottle, refusing money—“I have dogs too,” he said, not even knowing how important the timing of that one drink was. The handful of friends I told who said just the right thing, my landlord’s kind words of genuine empathy, my sister Becky getting up early to dig the grave at the family farm, my brother Dan taking the day off from work to help his adoring fur-friend out of this painful world, the vet who came to the farm on short notice to give her relief, and then peace. People who filled my heart and eyes at every turn, who sent Darcy messages of kindness I know she heard. Every dog lover’s dog is the best dog ever; Darcy was no different, except, of course, to me. But she was unusually intuitive, loyal, ever-patient, observant, and vigilant; a herd dog whose greatest goal was to keep an eye on her dwindling flock. She was unwaveringly devoted to me and the people I love. She went along with my every need—getting up at 4AM to walk under the stars, driving 14 hours to see the eclipse, waiting patiently under many a restaurant table. I never left her home alone for more than four hours, but she would lie at the window watching for me the entire time. She was so devoted to Tyler and Audrey that after they left for college, she lay by the front door for months, eyes fixed and ears pricked, listening for their return. Long after they moved to other states, even as recently as last week, she eagerly pulled me toward people who looked like them. Darcy never forgot a face or an experience; she learned everything with one try, from housebreaking to the hazards of chasing coyotes or snapping at rattlesnakes. She wasn't just smart; she was deeply intuitive and wise. Darcy assessed all kinds of situations with wisdom and accuracy. She was my radar, my barometer, my compass. I trusted her intuition even more than mine. She put her head on the laps of those she could tell were sad; in class, she chose to lie by the quietly anxious student. She knew which tense dogs to avoid and which ones she could calm. She once barked at me to “come,” then lay across a carpet cleaner’s feet, two times, barking insistently, her Batman-ears up and her eyes fixed brightly on me, to predict the massive coronary he would have before he got out of the driveway. Darcy really was the best dog ever. I will never be without my sweet girl. She was with me through the best and worst times of my life, and I was with her through hers. That didn’t stop when she breathed her last, and it won’t stop when I breathe mine.

19 Comments

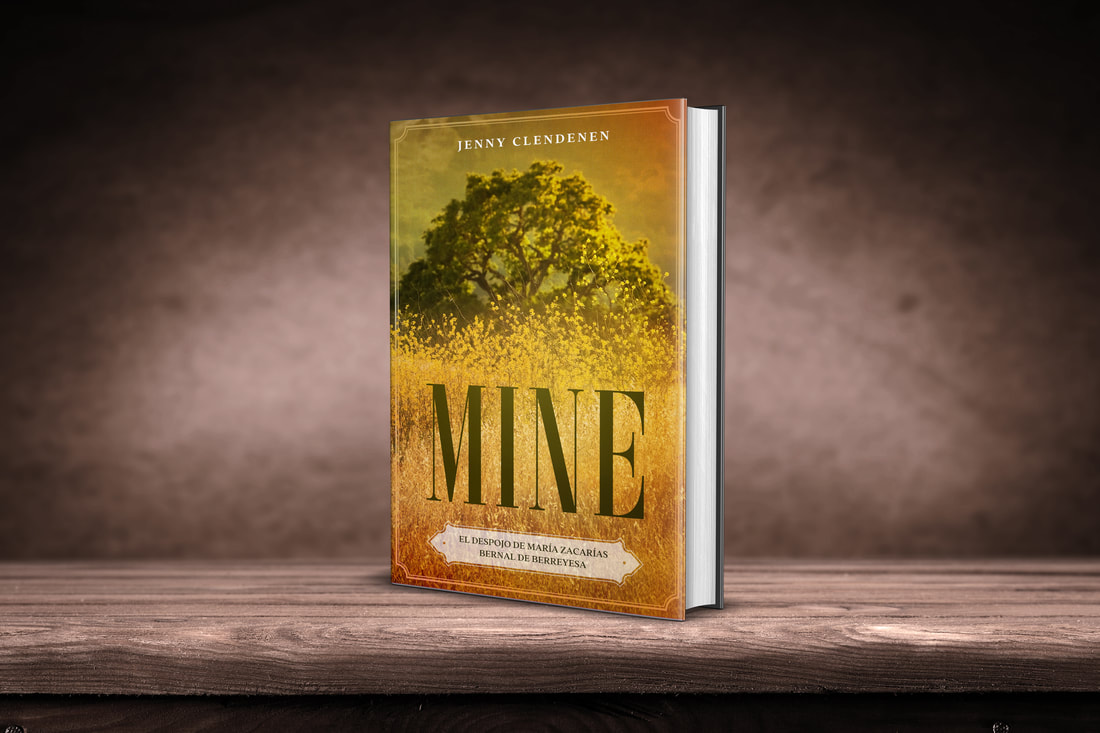

Happy Mother’s Day! This baby took eight years of labor, but today my book is finally out, and María Zacarías Bernal de Berreyesa gets to breathe. It's perfect that Mother's Day falls on Día de la Madre this year, because MINE is the true story of this Spanish-Mexican mother of thirteen, whose San José land (with a mercury mine) was also, in many ways, mine. It's a journey across landscapes uniting two mothers born centuries and cultures apart. I'm sharing the introduction below, which tells how we met--143 years after she died--and why her tale of betrayal, murder, and greed seemed mine to tell. MINE brings untaught history to light, and restores a voice to María Zacarías, who deserves to be heard. It was a finalist in the 2020 San Francisco Writing Contest (creative nonfiction) and the California Historical Society 2014 Book Award Contest. I’m excited and honored by all the interest in this remarkable Californio mother, and I hope her story will resonate with you as well. ¡Feliz Día de las Madres, Zacarías !! From the introduction to MINE: El Despojo de Maria Zacarias Bernal Berreyesa Like most Californians, I grew up with a fourth-grade, mission-project vision of our state’s earliest history. For most of my life I remembered only bell towers, and gray-robed priests, and smallpox epidemics that had killed many Indians. I knew nothing of the Californios who had “owned” the land for seventy-plus years, of their permanent disruption by the massive influx of foreigners—whites, that is—after 1848. Research showed me what American greed cost Zacarías and her people, but my heart showed me who she was through our common land. Rancho San Vicente, so integral to Zacarías’s mid-life and livelihood, has felt like “mine” for decades. Most of it is still ranchland, except for the corner where my children’s grade school stands beside her creek. For hundreds of mornings, after dropping them off, I would walk the banks of Los Alamitos, soaking up its beauty, reflecting on my own rural childhood. Often, I took my children there to play after school, so their childhoods would hold the same kinds of memories as mine. After my teens began driving to high school and my chauffeur role came to an end, I went back to the creek with my dog, working through motherhood angst and mid-life loss. In that anxious, sorrowful state of mind I began to see glimpses of a story there, odd words and aberrant phrases scattered throughout the waters and woods. I noticed the green glossy surf of non-native periwinkle, the face of a snarling devil in the knots of an oak, the distorted scar of an arrow carved in a trunk. I heard crickets rasping in the middle of the day. I found rusted mattress springs beneath the weeds, rotted chunks of lumber sticking out of banks, and bits of tumbled brick beneath the silt. I saw vultures hunkering together on rocks in the creek, and paddles of prickly pear cacti poking through weeds. There was an ancient, massive cactus stand my dog refused to pass, and when I carried her past it, I felt her trembling. There were signs of a mystery at Los Alamitos, a tale of something significant under its skin. I became convinced that something momentous had happened there. It was like being in an empty gothic chapel, appreciating its simple grace, yet feeling there might be stolen relics wedged in the vaults, morbid stains in the splendid fretwork. I already knew of the extinct quicksilver mines in the mountains’ spurs, but I felt something else was embedded nearby, something deeper than mercury mine shafts and cinnabar caves—something richer than ore. The creek was connecting me to both the past and presence. Now and then I thought that my raw state of mind might be making me imagine things, until one day, while visiting the Almaden Quicksilver Mining Museum, I learned that the creek had once defined the western end of Rancho San Vicente, the home of María Zacarías Bernal de Berreyesa. Who was she? I asked. The short answer astounded me. I understood, in a flash, why Los Alamitos Creek had been speaking to me; I knew she too would have paced its banks, caught up in grief and loss. By then I had spent almost half my life on her league—in my children’s classrooms on the corner of the ranch, or down by the creek that bordered her land, or in the surrounding hills—and suddenly I knew she had been with me all along. I found longer answers to “who was she?” at tables and desks, enough history to know her story deserved to be told. But I found the real Zacarías in natural places, not pictures or print. I felt bound to her by “our” land. So I have told her tale of losses through connections of the heart, weaving our experiences together in situ, under the influence of places and seasons we have shared across time. In doing so I intend MINE to resonate across cultural and political lines, to create empathy for María Zacarías Bernal de Berreyesa as a mother and woman, and to deepen awareness of our state’s Spanish-Mexican roots. MINE was a finalist in the 2020 San Francisco Writing Contest (creative nonfiction) and the California Historical Society 2014 Book Award Contest. It also won departmental awards at San José State University. MINE is available in paperback on Amazon.

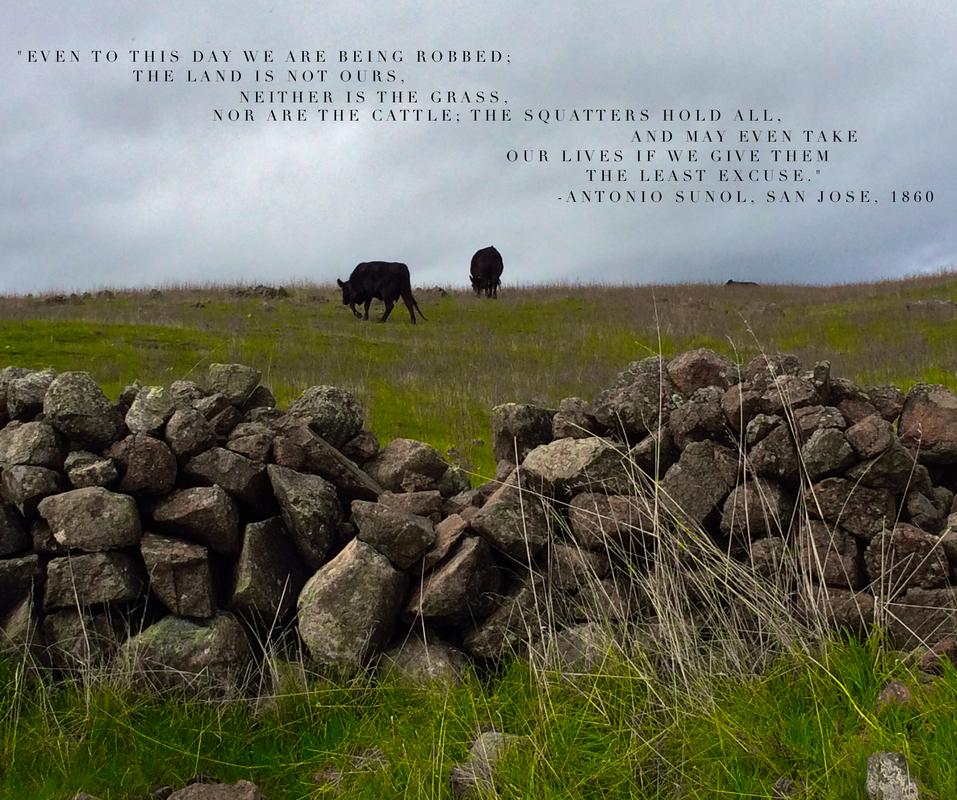

Zacarías's nephew, the younger Antonio Sunol, was killed by a squatter while patrolling the family’s rancho. The intruder had been haphazardly shooting at cattle until one dropped, wounding many, and Antonio, from his horse, had confronted him about the cruelty and waste. He had invited the shooter to come to his home and get all the meat he desired, but asked him to stop killing and wounding the cattle. In response, the squatter shot Antonio. His broken-hearted father, the senior Antonio, lost any vestiges of support he might have had for the American infiltration of California. - from MINE: El Despojo de María Zacarías Bernal de Berreyesa

226 years ago today, María Zacarías Bernal de Berreyesa was born in the presidio barracks of San Francisco. She almost didn't make it -- she was so near death at birth that she had to be rushed to the tiny chapel next door for an emergency baptism by the commandante. These are the ruins of the chapel where she was "saved" -- her soldier father, Joaquin Bernal, may have laid these foundational stones as one of his duties. I'm celebrating her birthday, her survival, and the completion of my book with a sangria at the Presidio Officer's Club, just a few feet away from the barracks and chapel sites. Today seems like a good day -- and this seems like the perfect place -- to begin sharing bits of her story with you. Here's a scrap from the prologue of MINE, about the night she was born and baptized, November 5, 1791: Candlelight quivers across a bloodstained bed, where a weary-eyed woman is curled on her side, watching a midwife bend over a silent bundle. A sweating young soldier stands inside the door, turning his hat in his hands. Voices drift through the glassless windows, the brief worried questions of relatives--¿esta bien? ¿Aun vive?—the murmur of women, and the whimpering of the newborn’s two sisters. I can hear the disconsolate squawks of wet chickens, the rumble of waves on the nearby shore, the rain that falls through the thatched roof and thuds on the floor. The baby has been born instantem periculum mortis, in danger of immediate death, and might not live long enough to be baptized at Mission Dolores four miles off—not even long enough to send for a priest.  This photo was taken by Mary Lovely, a lovely stranger who listened with enthusiasm as I explained while I'm here. Thanks for listening, Mary.)  It's been an educational, vertebrae-crunching six years, but MINE: El Despojo de María Zacarías Bernal de Berreyesa is now off to my hoped-for publisher and SJSU! Here's a little intro to Zacarías and her tale.

María Zacarías Bernal de Berreyesa was a Spanish-Mexican matriarch of early San José. The Bernals and Berreyesas had arrived in San Francisco in 1776, and helped settle the Bay Area throughout the mid-1800s; Zacarías’s father and husband were ranchers of neighboring estates in San José, and the hides-and-tallow trade had made them rich. But in 1846 John C. Frémont came to town, and began his destruction of Zacarías’s world. With his support (if not instigation), the Bear Flaggers revolted and captured three of her sons. When her husband rode north to check on their welfare, he was murdered by Kit Carson, acting on Frémont’s order. When the Gold Rushers swarmed in three years later, the widow’s land ownership was questioned—as were all Californio claims of land ownership. Zacarias, though, had a quicksilver mine on her land, and that metal made gold much easier to refine. Mercury rose in price, and sixty claimants rose against her—squatters, capitalists, and their lawyers. Even President Lincoln sent men to claim the mine, but she held her ground all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1863 the mine operations were decided to be on her rancho, but by the time that league of land was affirmed to be hers, it had been sold to cover legal bills. Financial losses were meaningless, though, because by then she had also lost nine of ten sons—some of them to violence and vigilante mobs, fueled by the tensions over the land and mines—seven sons gone in one turbulent decade alone. It is our overlapped places and fears that connect Zacarías and me. Rancho San Vicente, so integral to her life and livelihood, has felt like “mine” for decades. It is still open land, except for the corner where my children’s grade school stands, and I have spent countless hours along her creek, journaling my thoughts and worries. So I have told Zacarías’s tale of losses through connections of the heart, weaving our experiences together in situ to “ground” our empathy, playing out our stories on our common stage, under the influence of places and seasons we have shared across time. Like most Californians, I grew up with a fourth-grade, mission-project vision of our state’s earliest history: I remembered only bell towers, and gray-robed priests, and smallpox epidemics that had killed many Indians. I knew nothing of the Californios who had “owned” the land for seventy-plus years, of their permanent disruption by the massive influx of foreigners—whites—after 1848. Research showed me what American greed cost Zacarías and her people, but my heart showed me who she was through places and sons. I have looked at her life through the lens of our love for both. MINE is intended to resonate across cultural and political lines, to create empathy for Zacarías as a mother and woman, and to deepen awareness of our state’s Spanish-Mexican roots. This is an excerpt from the book I'm writing about the extraordinary life of a local Spanish-Mexican matriarch, a first generation colonist of San Jose. I wanted to share bits and pieces as I go, with the caveat that, like all works in process (and life), it's subject to change.

At eight o’clock in the morning, I am the only person on the trail beside Los Alamitos Creek. It is sunny and clear, with enough of a breeze to make faint songs of leaves. New light shimmers on night-moistened chaparral. The oaks are dark and lush. Sycamore branches, heavy with glossy green foliage, drape to the ground and rest there in jagged swoops, like the handkerchief hem of a gown. Their hole-punched bark and three-toed leaves lie all across the trail. Poison oak vines, pink with sun, encircle trunks. There are patches of darkness on Los Alamitos, places the sun gives only a passing glance. In summer fish linger within these mossy pools, watching for fallen mosquitos and hiding from herons. Today I, too, am drawn to shadowed places, to the bank where my boy once played in the shade of an oak. I have named this oak the Wailing Windblown Woman because, like the famous picture that can be seen as either a beauty or a hag, its shape can take two forms. Its tall trunk curves like an arcing spine, and its limbs grow laterally in one direction. I can see her as a woman facing a strong wind, her arms outstretched behind her, her hair and skirt blown back, reveling in nature’s power. Or I can see her as turned the other direction, a woman bent over in grief, her hair hanging down in her face, her arms reaching forward in supplication. Today I see her as Windblown Woman, because I am looking for strength, and the birds are singing in sweet staccato trills. In late August of 1842, on a warm day like this, Zacarias might have been doing her wash at this creek, or at least supervising the Indian servants who did – servants whose “payment” was typically room, board, and clothes. But for time I would see them all now, carrying stacks of soiled linens from the rickety carreta down to the shallow creek. A pair of yoked oxen would be snuffling and stamping at flies. The shouts of vaqueros and thudding of hooves would be drifting from the plain. There would be a picnic spread over the banks, sure to include tortillas, tomatoes, olives, figs, and beef. The air would be fragrant with food and homemade soap, along with the constant scent of hot weeds and manure. The girls and women would be standing in the creek, scrubbing the linens against the stones. Snowy white linens were the pride of every Spanish-Mexican family, and the doñas and daughters wore white except in mourning; families being large, this was all too often the case. Zacarias might be sitting on this very boulder, keeping one eye on eleven-year-old Domingo and nine-year-old Magdalena, and one eye out for intruders. Her grown daughters Loreta and Carmen, whose double wedding three years earlier had already produced three girls, might have been there with both surviving babies in arms, as might have Santiago’s pregnant wife, with their one living child, and numerous nieces and nephews and cousins as well. Today Zacarias’s older sons would be helping their father on the ranch. Reyes might not be quite himself; he had received Governor Alvarado’s confirmation of his land grant on the 20th – the prefect of Monterey had vouched for his character, recommending confirmation on the basis of “the honesty, numerous family, and good services of Señor Berryessa”– but only for one league, not two. For eight years he had been unable to claim the title to the two leagues granted him by Governor Figeuroa, who had since died; a neighbor, Justo Larios, was still contesting the boundaries. It was a frustrating situation, and one of more critical import than Reyes knew. * * * I return to the stream in the afternoon, when the sun is sliding behind the sycamores, and the gnats are rising up in languid drifts. Zacarias would be heading homeward now, the creaky carreta loaded with stacks of folded white linens, laundry supplies, and leftover picnic fare. I imagine Domingo, perhaps the only son still home all day, walking beside his middle-aged mother, holding her elbow as she steps around thistles and stones. He is the tenth boy of ten, born in 1830, six weeks before Ignacio’s wedding day. Zacarias had held her last son in her arms while her first son danced in his bride’s. An unexpected breeze disturbs the Windblown Woman. Pollen drifts down around me in clouds, sifting back and forth until it lands in the shaded creek. The water flinches. Maybe the woman is wailing after all. This is an excerpt from the book I'm writing about the extraordinary life of a local Spanish-Mexican matriarch, a first generation colonist of San Jose. I wanted to share bits and pieces as I go, with the caveat that, like all works in process (and life), it's subject to change. Fog swirls over the six-by-six excavation. A rusted metal liner surrounds some serpentinite stones, each scabbed with bronze moss and edged with tufts of weeds. The allure to archaeologists would be unclear, but for the white words stenciled inside the frame: PRESIDIO DE SAN FRANCISCO, 1780 CHAPEL, NAVE and ALTAR. This is a piece of the chapel’s foundation -- the place where a commandante once saved a little girl’s soul. Long before I had ever heard of Maria Zacarias Bernal Berreyesa, I intimately knew her rural league of land in south San Jose. The former Rancho San Vicente lies between two ranges near my home in the foothills, and my children attended school on a developed corner of the old ranch, just a stone’s throw from the creek along its border. On warm afternoons I would pick them up and take them directly to Los Alamitos to rinse away the day’s restraints, to feed ducks, build dams, and skim stones. But I would visit most often with my dog at dawn or dusk, when I heard only water, wind, and birds, and saw only creatures too cautious to come very close – though sometimes a rabbit or bobcat would dart from the shrubs. It was a place of solitude and meditation, where I was reminded that nothing is wasted or ugly or meaningless -- that new life always grows from the broken, fallen, old, and scarred. And the land was my touchstone when suburbia threatened my soul. In the twenty-four years I had been walking the two-mile loop around Los Alamitos Creek, I had noticed too many oddities not to wonder what might haunt it. The property exuded a known history through its rusted found objects and proximity to old quicksilver mines, but I was certain something else was embedded there, something deeper than mercury mine shafts and cinnabar caves, something richer than ore. I was intrigued by the stories I saw in particular places. The dark green surf of non-native vinca flooding a bank, the face of a snarling devil in the knots of an oak, a vignette of small animal skulls aligned in the mud. Places in the path where my dog refused to go, and when carried there, she trembled in my arms. The distorted scar of an arrow carved in a trunk. Crickets creaking in the middle of the day, frogs croaking at dawn, vultures hunkering together on rocks in the middle of the creek. Rusted mattress springs. Rotted chunks of lumber, bits of tumbled brick, a metal cart beneath the gritty silt. Thick paddles of cactus poking through patches of weeds. Unlikely pedestrians had also piqued my interest over the years. I repeatedly encountered people who did not conform to the standard suburban scene: A muttering woman with long silver hair wearing gypsy skirts and Keds, perpetually walking local streets and trails – a woman I had seen in my childhood, too, incessantly tracing another county’s veins . A hulking, sixty-something man preceded by five loose Chihuahuas; he introduced himself as a native Czech jazzman who ice skates at sunrise each day at the local rink. And then there was Ray, a convivial, middle-aged man whose grin, ponytail, and John Lennon glasses made him seem forever (and happily) stuck in the Summer of Love. The collective, recurring nature of these anomalies had always implied mystery along the creek, an impression of something significant under its skin. It was like being in an empty gothic chapel, where all is in perfect order and exudes simplistic grace, yet one senses hidden things wedged in the vaults, invisible stains seeping in through the fretwork. The beauty and peace of the place might still provide comfort -- but the aberration nonetheless exists, residual baseness permeating art. One fortunate day, Mary Berger and Heidi McFarland of the Almaden Quicksilver Mining Museum put a name to that sense. It did not surprise me to learn that the land that had been so meaningful to me had been of enormous significance to another woman – in fact, to the nation. But what Mary and Heidi told me about her life prickled my skin and touched my heart. What I learned from her great-nephew, San Jose's official historian and Superior Court judge Paul Bernal, sparked my quest. Together, their words began a journey that has led me here today, searching for Maria Zacarias.

Thank you for reading this excerpt from MINE -- your comments are always welcome! If you'd like to know when I post another, please subscribe for updates. |

Welcome to

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed