To see the intended line breaks of this poem, choose the desktop view on smaller devices.

A Split Tale

by Jenny Clendenen

with deep gratitude to Rachael and Suzanne Andersen, and all of Tokitae's supporters.

with deep gratitude to Rachael and Suzanne Andersen, and all of Tokitae's supporters.

Her body pulses with potential power, but for now

she floats in quiet, protected peace,

still attached to her mother, suspended in the dark liquid wild.

Suddenly she feels her mother thrash, and hears her cry out.

A brutal assault forces

mother from child and child from mother,

bloodying the waters in two locations, years and miles apart:

in the depths of a Puget Sound cove on August 8, 1970,

and in the shallows of a Monterey motel on Easter Sunday, 1994.

These dual dramas will connect across species and decades and along the Pacific coast

to reverberate between two scarred daughters--

surviving soul sisters who will one day help heal each other.

Her body pulses with potential power, but for now

she floats in quiet, protected peace,

still attached to her mother, suspended in the dark liquid wild.

Suddenly she feels her mother thrash, and hears her cry out.

A brutal assault forces

mother from child and child from mother,

bloodying the waters in two locations, years and miles apart:

in the depths of a Puget Sound cove on August 8, 1970,

and in the shallows of a Monterey motel on Easter Sunday, 1994.

These dual dramas will connect across species and decades and along the Pacific coast

to reverberate between two scarred daughters--

surviving soul sisters who will one day help heal each other.

|

The Washington daughter is an orca calf,

four years old and two tons in weight. She is lashed to the side of a boat in a net, to be sold to the Miami Seaquarium, over the piercing shrieks of her desperate mother, Ocean Sun, whose attempts to save her had failed. |

The California daughter is an infant

three months’ premature, two pounds in weight. She is wrapped in a blanket and placed in a car, to be given to Suzanne and Gary Andersen, an adoption arranged before her desperate mother, “Amber,” attempted to abort her and failed. |

The baby and the calf are twenty-four years apart.

They will not meet in person for another twenty-four years,

but they are already joined, two flukes of survival

converging in a single tale.

They will not meet in person for another twenty-four years,

but they are already joined, two flukes of survival

converging in a single tale.

The four-year-old is taken one bright summer morning from her home in the Salish Sea,

kidnapped for profit from her mother and her matriarchal group, known as L-pod,

by Edward Griffin and Donald Goldberry,

hunters for marine parks all over the profit-first world.

Orca hunting is a lawless enterprise in the 1960s and 70s,

though a treaty is supposed to protect Lummi Nation waters--

just one more American promise cast aside.

Griffin and Goldberry (names connoting hunters with talons, and secreted loot)

have stolen dozens of orca calves from their undersea homes.

After they are sold for profit and delivered as products,

these greatest of dolphins, born to swim

a hundred-plus miles each day

at twenty-eight miles per hour,

and to dive three hundred feet of cold ocean to catch live prey,

are put into chlorinated pools and taught tricks for dead fish.

kidnapped for profit from her mother and her matriarchal group, known as L-pod,

by Edward Griffin and Donald Goldberry,

hunters for marine parks all over the profit-first world.

Orca hunting is a lawless enterprise in the 1960s and 70s,

though a treaty is supposed to protect Lummi Nation waters--

just one more American promise cast aside.

Griffin and Goldberry (names connoting hunters with talons, and secreted loot)

have stolen dozens of orca calves from their undersea homes.

After they are sold for profit and delivered as products,

these greatest of dolphins, born to swim

a hundred-plus miles each day

at twenty-eight miles per hour,

and to dive three hundred feet of cold ocean to catch live prey,

are put into chlorinated pools and taught tricks for dead fish.

The infant is driven this foggy spring Sunday to the hospital in Monterey,

where her birth mother drops her off, then calls Suzanne and Gary.

The adoption had been arranged just the week before,

the culmination of strange synchronicities.

Amber, six months’ pregnant, had just watched a Barbara Walters show

featuring Suzanne’s sister as the victim of an Oklahoma adoption scam.

In one brief scene, a notepad on a table showed a handwritten telephone number.

Amber jotted it down, guessed at the area code, and reached Suzanne’s mother.

I’ll give your daughter my baby when it’s born, Amber offered,

but was told there was no longer a need.

But, said Suzanne’s mother, my other daughter might be interested.

Suzanne and Gary, childless so far,

had believed their prayers were being answered in a crazy yet wonderful way,

and with hearts (if not eyes) wide open, they had agreed to adopt Amber's baby.

But a few days later, Amber had decided to abort;

the doctors refused, so she had tried to do it herself.

where her birth mother drops her off, then calls Suzanne and Gary.

The adoption had been arranged just the week before,

the culmination of strange synchronicities.

Amber, six months’ pregnant, had just watched a Barbara Walters show

featuring Suzanne’s sister as the victim of an Oklahoma adoption scam.

In one brief scene, a notepad on a table showed a handwritten telephone number.

Amber jotted it down, guessed at the area code, and reached Suzanne’s mother.

I’ll give your daughter my baby when it’s born, Amber offered,

but was told there was no longer a need.

But, said Suzanne’s mother, my other daughter might be interested.

Suzanne and Gary, childless so far,

had believed their prayers were being answered in a crazy yet wonderful way,

and with hearts (if not eyes) wide open, they had agreed to adopt Amber's baby.

But a few days later, Amber had decided to abort;

the doctors refused, so she had tried to do it herself.

On Saturday morning the eighth of August in 1970,

the two hunters use spotter planes, motor boats, seal bombs, harpoon guns, and tranquilizer darts

to herd a superpod of Southern Resident orcas into Penn Cove at Whidbey Island,

trapping almost a hundred supersized dolphins there.

Residents and summertime tourists watch in shock

as the peaceful waters froth with opposing intentions.

Orca calves, disoriented by sonar-disrupting bombs,

are chased down and wedged apart from their mothers with rods.

The young are captured in nets and tied to the sides of boats,

as their frantic mothers ram their faces into the hulls.

chew at the ropes, and cry out to their terrified calves.

Ocean Sun nuzzles her calf and tries to force off the noose--

the capturing diver who watches her describes it, much later,

as an act of beauty and courage, intelligence and athletic skills.

He and other divers, and all of the horrified watchers,

will remember forever the orca’s anguished cries,

her vigil beside the capture pen,

the two crying out to each other in fear and distress.

A news commentator at the scene hears the sounds

as “sorrowful tones,” and “grieving cries, tearing at you.”

Children on shore scream out their frustration and grief.

That night four calves are tangled in nets and drown;

the hunters slice up and weigh down the bodies to hide them,

but the mutilated babies wash up on shore and further the public outrage.

A fifth orca, a mother, dies from her injuries.

Six of the seven calves kidnapped that day will die as captives

in Texas, Australia, France, England, Germany, and Japan.

The only survivor is Ocean Sun’s calf,

who will get a life sentence of confinement

in the Miami Seaquarium’s antiquated, undersized pool.

the two hunters use spotter planes, motor boats, seal bombs, harpoon guns, and tranquilizer darts

to herd a superpod of Southern Resident orcas into Penn Cove at Whidbey Island,

trapping almost a hundred supersized dolphins there.

Residents and summertime tourists watch in shock

as the peaceful waters froth with opposing intentions.

Orca calves, disoriented by sonar-disrupting bombs,

are chased down and wedged apart from their mothers with rods.

The young are captured in nets and tied to the sides of boats,

as their frantic mothers ram their faces into the hulls.

chew at the ropes, and cry out to their terrified calves.

Ocean Sun nuzzles her calf and tries to force off the noose--

the capturing diver who watches her describes it, much later,

as an act of beauty and courage, intelligence and athletic skills.

He and other divers, and all of the horrified watchers,

will remember forever the orca’s anguished cries,

her vigil beside the capture pen,

the two crying out to each other in fear and distress.

A news commentator at the scene hears the sounds

as “sorrowful tones,” and “grieving cries, tearing at you.”

Children on shore scream out their frustration and grief.

That night four calves are tangled in nets and drown;

the hunters slice up and weigh down the bodies to hide them,

but the mutilated babies wash up on shore and further the public outrage.

A fifth orca, a mother, dies from her injuries.

Six of the seven calves kidnapped that day will die as captives

in Texas, Australia, France, England, Germany, and Japan.

The only survivor is Ocean Sun’s calf,

who will get a life sentence of confinement

in the Miami Seaquarium’s antiquated, undersized pool.

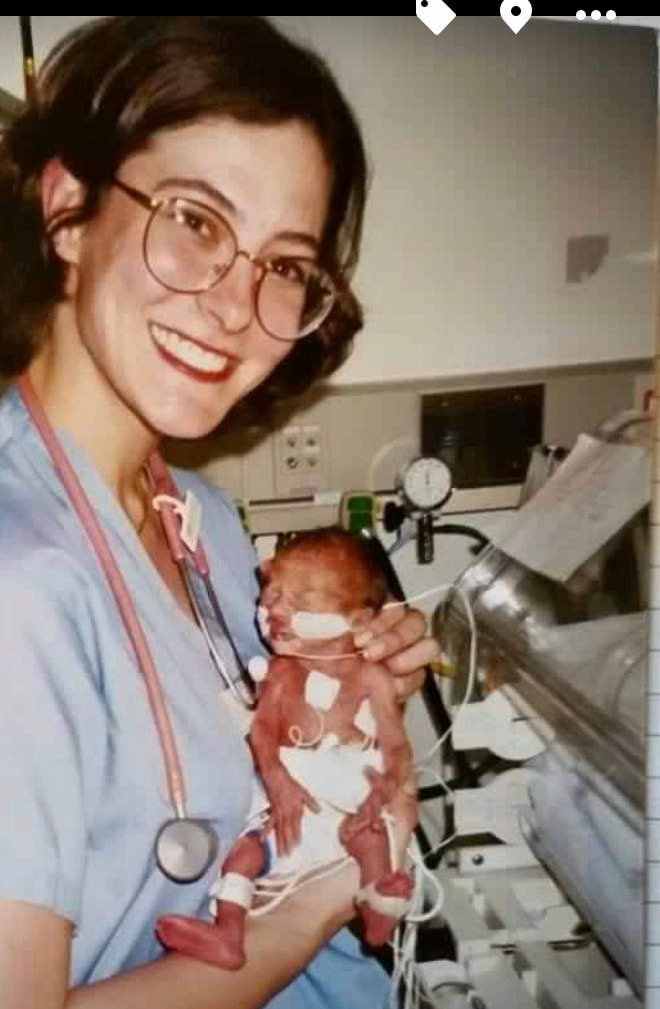

On this Easter Sunday, the third day of April in 1994,

hospital tests show the preemie is substance-dependent.

Amber had never disclosed her misuse of

opiates, nicotine, alcohol, meth, and cocaine.

The newborn shudders, stiffens, vomits, sweats, bucks her body, and screams.

She is swaddled and taken by ambulance two hours north,

to the Stanford Neonatal Intensive Care Unit.

Her first outdoor breath is of the damp brined air, of the scent of saltwater and sand;

her first drive is along the tan and silver coast lined with ice plant and pampas grass plumes,

then east through dense burgundy pillars of redwood trees.

In the years ahead, these scents and sights will nourish her heart and mind, her body and soul.

At Stanford, the nurses and doctors are blunt in their warnings,

but Suzanne and Gary, armed with faith, hope, and love, commit.

They each pick up the two-pound girl in their palms and press their heartbeats to hers,

beginning the newborn’s recovery.

In a month she will be moved to a Santa Cruz ICU, where she must stay until she reaches four pounds.

Then she can go home with the Andersens, as their daughter.

hospital tests show the preemie is substance-dependent.

Amber had never disclosed her misuse of

opiates, nicotine, alcohol, meth, and cocaine.

The newborn shudders, stiffens, vomits, sweats, bucks her body, and screams.

She is swaddled and taken by ambulance two hours north,

to the Stanford Neonatal Intensive Care Unit.

Her first outdoor breath is of the damp brined air, of the scent of saltwater and sand;

her first drive is along the tan and silver coast lined with ice plant and pampas grass plumes,

then east through dense burgundy pillars of redwood trees.

In the years ahead, these scents and sights will nourish her heart and mind, her body and soul.

At Stanford, the nurses and doctors are blunt in their warnings,

but Suzanne and Gary, armed with faith, hope, and love, commit.

They each pick up the two-pound girl in their palms and press their heartbeats to hers,

beginning the newborn’s recovery.

In a month she will be moved to a Santa Cruz ICU, where she must stay until she reaches four pounds.

Then she can go home with the Andersens, as their daughter.

The orca calf is moved from the net to a canvas sling,

hoisted by crane to the bed of a flatbed truck,

then loaded on a plane to be flown three thousand miles.

She is dubbed Tokitae by a Miami marine mammal veterinarian

who had seen the carved word in a curio shop in Seattle.

In Coast Salish tongue, it is a greeting: “Nice day, pretty colors.”

But there are no nice days in Miami, and no pretty colors;

no shade from the Caribbean sun, no cool ocean currents,

no shimmering salmon in the eelgrass, no fringe of fir at the shore,

no regal cedars on snow-frosted mountains beyond.

There is only a small tank of chlorinated water filtered in from the Bay of Biscayne,

with a view of some bleachers beneath a rusted roof.

hoisted by crane to the bed of a flatbed truck,

then loaded on a plane to be flown three thousand miles.

She is dubbed Tokitae by a Miami marine mammal veterinarian

who had seen the carved word in a curio shop in Seattle.

In Coast Salish tongue, it is a greeting: “Nice day, pretty colors.”

But there are no nice days in Miami, and no pretty colors;

no shade from the Caribbean sun, no cool ocean currents,

no shimmering salmon in the eelgrass, no fringe of fir at the shore,

no regal cedars on snow-frosted mountains beyond.

There is only a small tank of chlorinated water filtered in from the Bay of Biscayne,

with a view of some bleachers beneath a rusted roof.

Six weeks later, Suzanne and Gary carry their new daughter,

named Rachael Grace, into their small warm home in the Santa Cruz mountains.

They lay her in a crib filled with pink-and-white bedding,

under a quilt made of lace, with a rose in the middle

—her nickname will one day be Rose, for the beauty she brings.

Children’s books about animals lean on the shelves.

Trees wave and whisper outside the nursery window.

named Rachael Grace, into their small warm home in the Santa Cruz mountains.

They lay her in a crib filled with pink-and-white bedding,

under a quilt made of lace, with a rose in the middle

—her nickname will one day be Rose, for the beauty she brings.

Children’s books about animals lean on the shelves.

Trees wave and whisper outside the nursery window.

In the daytime, she floats listlessly. She does not swim or eat for several days.

An Aquamaid says that at night, the new orca cries.

She bobs up and down, up and down, up and down

as if looking for the rest of her pod.

The skin on her back cracks and bleeds.

A janitor takes pity, rigs up a shelter, and rubs her with lanolin.

An Aquamaid says that at night, the new orca cries.

She bobs up and down, up and down, up and down

as if looking for the rest of her pod.

The skin on her back cracks and bleeds.

A janitor takes pity, rigs up a shelter, and rubs her with lanolin.

In the daytime, she sleeps held close to Suzanne's heart..

But at night, besieged by colic, Rachael cries.

She quiets only when her dad holds her over his forearm

and bobs her up and down, up and down, up and down

like a boat bouncing over the waves.

Every morning Suzanne rubs her daughter with lotion and sings.

But at night, besieged by colic, Rachael cries.

She quiets only when her dad holds her over his forearm

and bobs her up and down, up and down, up and down

like a boat bouncing over the waves.

Every morning Suzanne rubs her daughter with lotion and sings.

Tokitae’s first trained acts are rote responses to human demands, in exchange for dead fish.

She is taught to breach on cue, wave a pectoral fin, and backflip to splash the crowd.

She has no choice, except to starve.

Her trainers teach her myriad tricks to please a paying crowd,

as the Seaquarium wants all it can get from its biggest attraction.

She is taught to breach on cue, wave a pectoral fin, and backflip to splash the crowd.

She has no choice, except to starve.

Her trainers teach her myriad tricks to please a paying crowd,

as the Seaquarium wants all it can get from its biggest attraction.

Rachael’s first smiles and words are responses to nature, to scrub jays, spiders, and squirrels.

As she grows she plants gardens, paints rainbows, and ponders what she will become:

paleontologist, beekeeper, veterinarian, astronaut, artist, gardener, mom.

Suzanne nurtures Rachael’s myriad interests in hands-on, wholehearted ways.

There is nothing she would not do for her cherished child.

As she grows she plants gardens, paints rainbows, and ponders what she will become:

paleontologist, beekeeper, veterinarian, astronaut, artist, gardener, mom.

Suzanne nurtures Rachael’s myriad interests in hands-on, wholehearted ways.

There is nothing she would not do for her cherished child.

Tokitae’s stolen, terrible life is lived in the smallest whale bowl in the nation,

a pool not even as deep as she is long, where she turns tight circles under a tropical sun.

Her soul calls for her mother and the rest of her family, who live in

the inland waters of the Pacific, from British Columbia south to Puget Sound.

She is young and yet she has seen so many grand things:

Earth’s largest octopus, barnacle, anemone, jellyfish, chiton, and sculpin.

She has wondered at creatures, from sand crabs to “killer whales”

(in fact, Southern Resident orcas kill only salmon)

and at all that wiggles and swims in the Salish Sea.

a pool not even as deep as she is long, where she turns tight circles under a tropical sun.

Her soul calls for her mother and the rest of her family, who live in

the inland waters of the Pacific, from British Columbia south to Puget Sound.

She is young and yet she has seen so many grand things:

Earth’s largest octopus, barnacle, anemone, jellyfish, chiton, and sculpin.

She has wondered at creatures, from sand crabs to “killer whales”

(in fact, Southern Resident orcas kill only salmon)

and at all that wiggles and swims in the Salish Sea.

Rachael’s salvaged, nurtured life is lived out of doors,

whether in cathedrals of redwoods by fern-laced creeks,

or at the beach, where she would spend every day if she could.

That primal junction of earth and sea is where body meets soul,

for the planet and also for Rachael.

She is little and yet she intuits grand things:

the ideas of freedom in the sweep of a gull, of joy in the yelp of a seal.

She feels at one with all creatures, from sand crabs to whales.

She senses the presence of Godness in all of nature,

but mostly in all that wiggles and swims in the sea.

whether in cathedrals of redwoods by fern-laced creeks,

or at the beach, where she would spend every day if she could.

That primal junction of earth and sea is where body meets soul,

for the planet and also for Rachael.

She is little and yet she intuits grand things:

the ideas of freedom in the sweep of a gull, of joy in the yelp of a seal.

She feels at one with all creatures, from sand crabs to whales.

She senses the presence of Godness in all of nature,

but mostly in all that wiggles and swims in the sea.

At five years old Rachael gets two big surprises:

a baby sister,

and a trip to SeaWorld in San Diego, with a friend from kindergarten.

There the Shamu Adventure show makes her shiver with awe.

She watches the performance over and over all week,

mesmerized by the orca’s intelligence, beauty, and power.

She is only five; there are five years of innocence left,

twenty before she can forgive herself and say,

to herself and the uninformed world at large,

You just don’t know what you don’t know.

When she gets home, she looks up facts about Orcinus orca.

She learns the “blackfish,” or “killer whale,” is neither a fish nor a whale.

a baby sister,

and a trip to SeaWorld in San Diego, with a friend from kindergarten.

There the Shamu Adventure show makes her shiver with awe.

She watches the performance over and over all week,

mesmerized by the orca’s intelligence, beauty, and power.

She is only five; there are five years of innocence left,

twenty before she can forgive herself and say,

to herself and the uninformed world at large,

You just don’t know what you don’t know.

When she gets home, she looks up facts about Orcinus orca.

She learns the “blackfish,” or “killer whale,” is neither a fish nor a whale.

It is the largest of dolphins, a highly intelligent mammal

with a central nerve cord and a spine.

Orca babies grow in a placenta, then emerge from the womb;

at birth they even have hair.

They cry and nurse from nipples.

If a calf is in danger, the mothers pair up to lift it high out of the water.

A family stays close at all times, always ruled by the matriarch.

Multiple families stick together in pods, and pods stick together in clans.

The mother bears children from fifteen to forty, but can live ninety years or more.

She is not only the source but the sustenance of her descendants.

What is more, she adopts orphaned calves.

with a central nerve cord and a spine.

Orca babies grow in a placenta, then emerge from the womb;

at birth they even have hair.

They cry and nurse from nipples.

If a calf is in danger, the mothers pair up to lift it high out of the water.

A family stays close at all times, always ruled by the matriarch.

Multiple families stick together in pods, and pods stick together in clans.

The mother bears children from fifteen to forty, but can live ninety years or more.

She is not only the source but the sustenance of her descendants.

What is more, she adopts orphaned calves.

Mothers are the backbone and heart of the family.

This truth, for her, is black and white.

This truth, for her, is black and white.

Tokitae remembers Ocean Sun, and their life in the Salish Sea.

Twenty-six years after they were forced apart,

a Dateline reporter at the edge of her pool plays a recording of L-pod calls--

the unique clicks, whistles, and pulses of her family’s dialect.

Tokitae instantly swims toward the man, rises vertically out of the water,

puts the side of her head to the speaker, and hops up and down.

She is visibly moved by the familiar, familial sounds of Puget Sound.

Twenty-six years after they were forced apart,

a Dateline reporter at the edge of her pool plays a recording of L-pod calls--

the unique clicks, whistles, and pulses of her family’s dialect.

Tokitae instantly swims toward the man, rises vertically out of the water,

puts the side of her head to the speaker, and hops up and down.

She is visibly moved by the familiar, familial sounds of Puget Sound.

What is she thinking, in that elegant brain with two lobes we humans don’t have?

Does her cingulate gyrus, like ours but much bigger and more complex,

process even more intense memories and feelings?

Does it, as some scientists think, transmit empathy?

Are her auditory and sensory processors helping her see?

Do the tonal whistles look like her brothers and sisters playing?

Is she hearing chatter about chinook salmon and rainbow trout?

Are the pulsed calls a birth announcement from clan to clan?

Or does she hear-feel danger, excitement, anger, or fear?

Are Ocean Sun’s echolocation clicks in the mix?

All we know is that Tokitae responds instantly to the sounds of her faraway clan,

and gives her family’s words her full, deep attention.

She seems to join them across three thousand miles of land.

Does her cingulate gyrus, like ours but much bigger and more complex,

process even more intense memories and feelings?

Does it, as some scientists think, transmit empathy?

Are her auditory and sensory processors helping her see?

Do the tonal whistles look like her brothers and sisters playing?

Is she hearing chatter about chinook salmon and rainbow trout?

Are the pulsed calls a birth announcement from clan to clan?

Or does she hear-feel danger, excitement, anger, or fear?

Are Ocean Sun’s echolocation clicks in the mix?

All we know is that Tokitae responds instantly to the sounds of her faraway clan,

and gives her family’s words her full, deep attention.

She seems to join them across three thousand miles of land.

Suzanne is the sun to Rachael’s ocean, the light on her love of the sea;

she does all she can to boost her girl’s salty glow.

She often takes her to the Monterey Bay Aquarium.

For Rachael’s sake she hosts Beach Clean-up Days,

when they work to clear the coastline of plastic and cans.

She hires a renowned artist to teach her daughter how to paint sea life,

then enters her artwork at Long’s Marine Lab and the Santa Cruz County Fair,

and proudly displays her blue ribbons.

She constantly feeds Rachael’s passion for all things marine,

and joins her in every adventure, tour, and task.

She also nurtures Rachael’s excellent visual talents and reading skills,

which inversely correlate to her auditory processing and sensory issues.

Rachael reads unceasingly about everything, but especially about nature,

and then she wants to experience everything “out of the book.”

Suzanne encourages her to adopt and care for all kinds of creatures,

from seven-legged spiders to wounded waterfowl.

Suzanne’s wholehearted support is rooted in love and watered by memory.

As a child she had felt forgotten, ignored, and rejected;

she had felt neither pretty nor smart.

Now she wants both of her own little girls

to receive all that she had once missed,

so she withholds nothing, neither love nor care,

not a moment of time nor a dime.

She vows her daughters will always feel important and wanted.

She vows her daughters will never feel ugly or stupid.

she does all she can to boost her girl’s salty glow.

She often takes her to the Monterey Bay Aquarium.

For Rachael’s sake she hosts Beach Clean-up Days,

when they work to clear the coastline of plastic and cans.

She hires a renowned artist to teach her daughter how to paint sea life,

then enters her artwork at Long’s Marine Lab and the Santa Cruz County Fair,

and proudly displays her blue ribbons.

She constantly feeds Rachael’s passion for all things marine,

and joins her in every adventure, tour, and task.

She also nurtures Rachael’s excellent visual talents and reading skills,

which inversely correlate to her auditory processing and sensory issues.

Rachael reads unceasingly about everything, but especially about nature,

and then she wants to experience everything “out of the book.”

Suzanne encourages her to adopt and care for all kinds of creatures,

from seven-legged spiders to wounded waterfowl.

Suzanne’s wholehearted support is rooted in love and watered by memory.

As a child she had felt forgotten, ignored, and rejected;

she had felt neither pretty nor smart.

Now she wants both of her own little girls

to receive all that she had once missed,

so she withholds nothing, neither love nor care,

not a moment of time nor a dime.

She vows her daughters will always feel important and wanted.

She vows her daughters will never feel ugly or stupid.

Tokitae’s tank is adjacent to a young male orca, an L-pod relation named Hugo,

a captive since 1968. He has long been beating his head on the concrete wall,

but Tokitae’s presence next door gives him reason to live.

It is frustrating not to be able to see one another,

so they squeal and whistle in unique L-pod vocalizations.

a captive since 1968. He has long been beating his head on the concrete wall,

but Tokitae’s presence next door gives him reason to live.

It is frustrating not to be able to see one another,

so they squeal and whistle in unique L-pod vocalizations.

Rachael plays all day long outside with her little sister, who becomes her best friend.

The girls are five years apart, but Suzanne schools them at home, so they do lots of projects together:

raising chickens, keeping bees, crafting gourds, arranging flowers, sewing quilts,

cooking jam, baking pastries. They enter their 4-H projects in the county fair.

They love to swim with their dad in their above-ground pool,

or far better yet, at the beach.

The girls are five years apart, but Suzanne schools them at home, so they do lots of projects together:

raising chickens, keeping bees, crafting gourds, arranging flowers, sewing quilts,

cooking jam, baking pastries. They enter their 4-H projects in the county fair.

They love to swim with their dad in their above-ground pool,

or far better yet, at the beach.

For this annoyance the Seaquarium dubs her their “Screaming Lolita,”

after Nabokov’s miserable heroine,

a child renamed and drugged and enslaved by a self-serving man,

a child who escapes to be prostituted by yet another.

A degrading name, yet miserably apropos.

As for Hugo, after years of beating his head against the wall of his tank,

he dies of a brain aneurysm.

Seaquarium has his big beautiful body removed by a crane

and dropped in the Miami-Dade dump.

His supporters call his death

a suicide.

after Nabokov’s miserable heroine,

a child renamed and drugged and enslaved by a self-serving man,

a child who escapes to be prostituted by yet another.

A degrading name, yet miserably apropos.

As for Hugo, after years of beating his head against the wall of his tank,

he dies of a brain aneurysm.

Seaquarium has his big beautiful body removed by a crane

and dropped in the Miami-Dade dump.

His supporters call his death

a suicide.

Gary and Suzanne are so proud of how kind Rachael is.

A family friend nicknames her “Rose,”

for having beautified so many lives.

The friend must have meant that Rachael was a bloom in a garden,

a growing plant that blossoms each year, not

a cut flower.

A family friend nicknames her “Rose,”

for having beautified so many lives.

The friend must have meant that Rachael was a bloom in a garden,

a growing plant that blossoms each year, not

a cut flower.

Seaquarium is proud of their captive’s profitable appeal.

Now called “Lolita,” she is robbed of health, happiness, freedom and family.

She is not allowed to exercise her inherent talents and speech.

She is given dead fish for tricks, and for suppressing her natural sounds—

for instead making noises like farts for a laughing crowd.

Now called “Lolita,” she is robbed of health, happiness, freedom and family.

She is not allowed to exercise her inherent talents and speech.

She is given dead fish for tricks, and for suppressing her natural sounds—

for instead making noises like farts for a laughing crowd.

A few workers know that at night in her blue concrete tank, Tokitae cries.

Rachael is nicknamed Rose for the sweetest of reasons,

though she would be just as sweet by any other name.

She has good health and happiness, freedom and family, talent in art and speech.

She is given all a girl can receive from outside of herself,

though her inside self is exacting a heavy toll.

though she would be just as sweet by any other name.

She has good health and happiness, freedom and family, talent in art and speech.

She is given all a girl can receive from outside of herself,

though her inside self is exacting a heavy toll.

No one knows that at night on the white vinyl floor of the bathroom, Rachael cries.

Stuck in the Seaquarium’s fishbowl,

Tokitae simply survives.

She can neither bolt nor fully breach nor dive.

Her flukes and fins rub the sides of her small, shallow pool.

She spends long hours floating motionless next to a valve,

bored out of her enormous mind.

She is blistered, wrinkled, and sunburned.

There is no shade, ever, from the hot Miami sun.

As with all captive dolphins, her elegant fin flops sideways.

Every day her sensitive ears are assaulted by loudspeakers blaring pop music,

and thousands of spectators screaming and clapping,

and jets descending to land at Miami-Dade,

and in the summer, fireworks exploding--

none of which echo the sounds of Puget Sound.

Tokitae simply survives.

She can neither bolt nor fully breach nor dive.

Her flukes and fins rub the sides of her small, shallow pool.

She spends long hours floating motionless next to a valve,

bored out of her enormous mind.

She is blistered, wrinkled, and sunburned.

There is no shade, ever, from the hot Miami sun.

As with all captive dolphins, her elegant fin flops sideways.

Every day her sensitive ears are assaulted by loudspeakers blaring pop music,

and thousands of spectators screaming and clapping,

and jets descending to land at Miami-Dade,

and in the summer, fireworks exploding--

none of which echo the sounds of Puget Sound.

When Rachael is ten, Suzanne takes her on a tour to watch orcas swim in the wild.

When the giants surge out of the sea to breathe, Rachael gasps--

as if she too had been running low on air.

She is bewitched by the orcas’ otherworldliness, yet they feel so familiar to her.

As she watches them dive and bolt and breach,

her spirit seems inside the ocean, at one with the pod.

This Moment changes everything.

That summer, her friend from her kindergarten days

invites her to SeaWorld again.

Rachael can hardly wait.

But this time the orca show causes her great distress.

It is hard to describe to her friend what is wrong;

she just knows that watching it makes her want to cry,

that she feels sick and dirty,

as if she has done something wrong.

She struggles to get past her revulsion, anxiety, and agitation.

She is a guest of her friend’s family, after all, and the plan is to stay here all week.

She works hard to go with the flow, but her body stays tense.

When the giants surge out of the sea to breathe, Rachael gasps--

as if she too had been running low on air.

She is bewitched by the orcas’ otherworldliness, yet they feel so familiar to her.

As she watches them dive and bolt and breach,

her spirit seems inside the ocean, at one with the pod.

This Moment changes everything.

That summer, her friend from her kindergarten days

invites her to SeaWorld again.

Rachael can hardly wait.

But this time the orca show causes her great distress.

It is hard to describe to her friend what is wrong;

she just knows that watching it makes her want to cry,

that she feels sick and dirty,

as if she has done something wrong.

She struggles to get past her revulsion, anxiety, and agitation.

She is a guest of her friend’s family, after all, and the plan is to stay here all week.

She works hard to go with the flow, but her body stays tense.

Tokitae is loaded on drugs to disguise her distress,

or to prevent infection from captivity-catalyzed damage.

She is given a drug used to treat stress-induced ulcers,

and two drugs to treat both fungal and skin infections.

Eye drops are regularly put in both cloudy eyes;

her right eye itches, tears, and swells

because of dust and UV radiation,

so she closes one or both eyes as she performs.

She is on a painkiller and, though too old to mate,

a dangerous birth control drug also used

to address polyps, cancer, ovarian cysts, and endometriosis.

Four antibiotics treat hundreds of rakes

by the two agitated Pacific white-sided dolphins

caged with her in the pool that is too small for even just them.

They chase and harass her often

(they may see her as a predator, since other kinds of orcas eat dolphins),

causing her much anxiety and agitation.

or to prevent infection from captivity-catalyzed damage.

She is given a drug used to treat stress-induced ulcers,

and two drugs to treat both fungal and skin infections.

Eye drops are regularly put in both cloudy eyes;

her right eye itches, tears, and swells

because of dust and UV radiation,

so she closes one or both eyes as she performs.

She is on a painkiller and, though too old to mate,

a dangerous birth control drug also used

to address polyps, cancer, ovarian cysts, and endometriosis.

Four antibiotics treat hundreds of rakes

by the two agitated Pacific white-sided dolphins

caged with her in the pool that is too small for even just them.

They chase and harass her often

(they may see her as a predator, since other kinds of orcas eat dolphins),

causing her much anxiety and agitation.

On the last day of the trip, Rachael’s friend’s mother takes them to the touch pools,

to let the two girls feed the dolphins from trays.

Rachael does not want to do it, but neither does she want to seem rude.

The dolphin she “feeds” is a sorrowful sight.

The animal’s eyes are cloudy and red, and his body is

covered from nose to tail in scratches and flaps of torn skin.

When he opens his mouth for the dead fish, Rachael can see the dolphin has no teeth.

When she asks why, the trainer gives an evasive response.

The ten-year-old is filled with horror and guilt.

She suddenly knows there is more missing here than teeth.

Someday she will shake her wiser head and say,

You just don’t know what you don’t know.

Rachael goes back to the hotel room and sobs.

Her friend is dismayed and perplexed,

but Rachael can’t explain the raw pain, the wound in her gut.

She only knows that the captive cetaceans

had contrasted in cruel, ugly ways

with the orcas she had seen in the wild a few months before.

She sees the relationship between humans and animals very differently now,

though it takes years to articulate that.

to let the two girls feed the dolphins from trays.

Rachael does not want to do it, but neither does she want to seem rude.

The dolphin she “feeds” is a sorrowful sight.

The animal’s eyes are cloudy and red, and his body is

covered from nose to tail in scratches and flaps of torn skin.

When he opens his mouth for the dead fish, Rachael can see the dolphin has no teeth.

When she asks why, the trainer gives an evasive response.

The ten-year-old is filled with horror and guilt.

She suddenly knows there is more missing here than teeth.

Someday she will shake her wiser head and say,

You just don’t know what you don’t know.

Rachael goes back to the hotel room and sobs.

Her friend is dismayed and perplexed,

but Rachael can’t explain the raw pain, the wound in her gut.

She only knows that the captive cetaceans

had contrasted in cruel, ugly ways

with the orcas she had seen in the wild a few months before.

She sees the relationship between humans and animals very differently now,

though it takes years to articulate that.

In 2016, a district judge orders Tokitae’s records revealed--

fifteen years’ worth, minus three years of records that are “missing”--

along with testimonies of four highly esteemed experts from around the world:

a veterinarian, a former senior SeaWorld trainer, an orca researcher, and a marine conservationist.

Tokitae is noted at least three hundred times to be tense or extremely tense.

Like other captive orcas, she breaks her teeth chewing on things.

Her teeth are given pulpotomies to take out soft tissue,

sometimes drilled for days on end, but even though bleeding,

the orca show must go on.

She tries to express her pain and strain:

She head-bobs a trainer,

tries to bite a trainer’s leg,

pushes a trainer into the pool.

No one is listening, though at least some are taking notes.

fifteen years’ worth, minus three years of records that are “missing”--

along with testimonies of four highly esteemed experts from around the world:

a veterinarian, a former senior SeaWorld trainer, an orca researcher, and a marine conservationist.

Tokitae is noted at least three hundred times to be tense or extremely tense.

Like other captive orcas, she breaks her teeth chewing on things.

Her teeth are given pulpotomies to take out soft tissue,

sometimes drilled for days on end, but even though bleeding,

the orca show must go on.

She tries to express her pain and strain:

She head-bobs a trainer,

tries to bite a trainer’s leg,

pushes a trainer into the pool.

No one is listening, though at least some are taking notes.

When Rachael returns to her home in the mountains,

she plunges into research again,

just as she had done after her first trip to SeaWorld five innocent years before.

This time, though, she turns to the Internet,

accessed in the dark of the family’s laundry room,

where, for lack of space anywhere else,

the primeval hard drive and boxy beige monitor are wedged--

the computer a box in a box in a box,

a hidden Pandoran portal to the wide-webbed world.

Rachael enters it at midnight, while her parents and sister sleep.

Surrounded by stacks of folded clothes,

her green eyes fix on the glowing curved screen and

her shoulders lean over the keys,

as she taps out phrases to open doors to facts:

how do marine parks catch orcas and dolphins

why do dolphins at seaworld have red eyes and no teeth

why is shamu’s dorsal fin flopp

she plunges into research again,

just as she had done after her first trip to SeaWorld five innocent years before.

This time, though, she turns to the Internet,

accessed in the dark of the family’s laundry room,

where, for lack of space anywhere else,

the primeval hard drive and boxy beige monitor are wedged--

the computer a box in a box in a box,

a hidden Pandoran portal to the wide-webbed world.

Rachael enters it at midnight, while her parents and sister sleep.

Surrounded by stacks of folded clothes,

her green eyes fix on the glowing curved screen and

her shoulders lean over the keys,

as she taps out phrases to open doors to facts:

how do marine parks catch orcas and dolphins

why do dolphins at seaworld have red eyes and no teeth

why is shamu’s dorsal fin flopp

Headlines and images splatter her screen, hitting her with physical force.

Emotions sink through her in shivery mixes and layers:

horror and anguish, compassion and anger, confusion and comprehension.

One story stands out,

of a sole survivor of a brutal round-up and theft in a Washington cove.

The truth surfaces and bolts through her mind

in stark black and white.

Rachael’s eyes widen; she shudders, then sobs

in psychosomatic pain.

She feels a luminous string unwind from her heart,

unfurl in a flash to the Florida tank,

and twine her to Tokitae.

Looking at her on the monitor screen is like seeing herself in a mirror:

Emotions sink through her in shivery mixes and layers:

horror and anguish, compassion and anger, confusion and comprehension.

One story stands out,

of a sole survivor of a brutal round-up and theft in a Washington cove.

The truth surfaces and bolts through her mind

in stark black and white.

Rachael’s eyes widen; she shudders, then sobs

in psychosomatic pain.

She feels a luminous string unwind from her heart,

unfurl in a flash to the Florida tank,

and twine her to Tokitae.

Looking at her on the monitor screen is like seeing herself in a mirror:

two lonely girls, apart and together, boxed in a tiny tank,

hurting through that moment as one and the same, and each day

suffering in silence while unaware trainers and spectators praise and applaud,

every night crying out in the dialects of misery and loss--

one in the speech of her mother’s pod,

the other in the language of tears--

Salish and saline expressions of loneliness.

One soul has stretched out and fused with the light of another’s.

From now on, the great dolphin in the small, shallow pool in Miami

and the bright, fragile girl in the forest by the Santa Cruz sea

will connect with each other in deep, inexplicable ways.

hurting through that moment as one and the same, and each day

suffering in silence while unaware trainers and spectators praise and applaud,

every night crying out in the dialects of misery and loss--

one in the speech of her mother’s pod,

the other in the language of tears--

Salish and saline expressions of loneliness.

One soul has stretched out and fused with the light of another’s.

From now on, the great dolphin in the small, shallow pool in Miami

and the bright, fragile girl in the forest by the Santa Cruz sea

will connect with each other in deep, inexplicable ways.

In 2007, when Rachael is twelve, Suzanne finds her a scuba-dive master,

and sheds her own fears to support Rachael’s certification.

She takes her to dive for trash at a coastal cleanup, then documents the day

and preserves her daughter’s thoughts, poems, and art in a spiral-bound book.

Rachael’s poems are pleas by marine life for a clean place to live,

for a habitat free of pollutants and debris such as Styrofoam, fish hooks, and cans.

She seems to speak both for and from the sea,

having spent hours among sponges, sea lions, anemones, and crabs.

In one photograph, wearing full scuba gear, she resembles a shiny black seal.

In another, taken after coming up from a thirty-foot dive,

an oval of rubber frames viridian eyes above an ample grin.

It’s clear Rachael takes to the ocean like—a fish to water.

She paints notecards of sea animals and sells them at shows for two years

to save money for a long-dreamed-of trip to Australia,

where she hopes to see the leafy sea dragon in its native home.

Suzanne adds to the stash by selling a treasured set of furniture,

and mother and daughter make the journey together.

On Rachael’s thirteenth birthday, she dives the Great Barrier Reef

with nurse sharks, sea turtles, bay rays, and leafy sea dragons.

and sheds her own fears to support Rachael’s certification.

She takes her to dive for trash at a coastal cleanup, then documents the day

and preserves her daughter’s thoughts, poems, and art in a spiral-bound book.

Rachael’s poems are pleas by marine life for a clean place to live,

for a habitat free of pollutants and debris such as Styrofoam, fish hooks, and cans.

She seems to speak both for and from the sea,

having spent hours among sponges, sea lions, anemones, and crabs.

In one photograph, wearing full scuba gear, she resembles a shiny black seal.

In another, taken after coming up from a thirty-foot dive,

an oval of rubber frames viridian eyes above an ample grin.

It’s clear Rachael takes to the ocean like—a fish to water.

She paints notecards of sea animals and sells them at shows for two years

to save money for a long-dreamed-of trip to Australia,

where she hopes to see the leafy sea dragon in its native home.

Suzanne adds to the stash by selling a treasured set of furniture,

and mother and daughter make the journey together.

On Rachael’s thirteenth birthday, she dives the Great Barrier Reef

with nurse sharks, sea turtles, bay rays, and leafy sea dragons.

Back in Santa Cruz, Suzanne keeps stoking Rachael's love of the sea.

She helps her daughter get a volunteer role

at the Monterey Bay Aquarium, one hour south,

and drives her to and from her weekly shifts.

Rachael is a Team Conservation Leader there, and a Volunteer Apprentice Guide.

She is “adopted” by mentors of grandparent age,

who help her give not just to creatures but to children as well.

Rachael loves inspiring kids to accomplish their goals and dreams.

Already a 4-H Community Service Chair, Rachael works with the Packard Foundation

to bring ten homeless children to visit the Aquarium,

where she fills their minds, hearts, and bellies in memorable ways.

Later she enlists those same kids to join her “Blankets of Love” project for children in the hospital--

the same hospital where she had stayed in the intensive neonatal care unit,

and had undergone heart surgery at twelve.

She knows those young beneficiaries can benefit others.

It really is more fun to give than receive, she says in a speech to Aquarium staff.

They give her a standing ovation, in awe that despite her fraught beginning,

she has done so much good for others by only age sixteen.

Suzanne, holding the video camera, beams.

She is so proud of her girl, so happy to see her caring heart given this honor.

She thinks of the substance-dependent baby

whose first years were a flurry of visiting nurses,

and is grateful to have passed through the whitecaps and reached these still waters.

She does not know strong winds and currents are gathering force.

Hurricane Irma slashes at the Florida shore,

a Category 4 storm when it reaches the abandoned orca.

Other parks have airlifted their charges to safety, including killer whales,

but not Seaquarium.

Tokitae is left to the screaming wind and the clattering of flying debris.

She is at risk of the stadium’s old metal roof being ripped off and striking her,

of her pool’s filtration and refrigeration systems being swamped,

of sewage poisoning the waters that supply her small tank.

Fortunately, the storm veers ninety miles west of Miami.

A drone shows Tokitae in murky brown water, still alive.

Two dolphins and other Seaquarium captives die.

a Category 4 storm when it reaches the abandoned orca.

Other parks have airlifted their charges to safety, including killer whales,

but not Seaquarium.

Tokitae is left to the screaming wind and the clattering of flying debris.

She is at risk of the stadium’s old metal roof being ripped off and striking her,

of her pool’s filtration and refrigeration systems being swamped,

of sewage poisoning the waters that supply her small tank.

Fortunately, the storm veers ninety miles west of Miami.

A drone shows Tokitae in murky brown water, still alive.

Two dolphins and other Seaquarium captives die.

At fourteen, a hurricane of hormones howls through Rachael’s mind,

raising a tidal wave of chemicals that toxifies her low reservoir of coping skills.

Her sense of being a misfit turns into self-loathing.

Suzanne anxiously notes days when her daughter eats nothing at all,

and days when she binges and then makes herself throw up.

Then Rachael starts waking up early, locking herself in the bathroom

to cut her legs.

Sometimes she carves entire ugly words in her skin.

The vicious swoops and sharp lines of STUPID bleed over her thigh,

a word that also slices her mother’s heart.

Suzanne, terrified, tries hard to figure out what has gone wrong.

She always tries to wipe up the blood before Rachael's sister awakes.

Several times, a friend helps her search the house for razor blades,

but each one they find is soon replaced by more.

So Rachael (because she cannot yet stop) goes on.

raising a tidal wave of chemicals that toxifies her low reservoir of coping skills.

Her sense of being a misfit turns into self-loathing.

Suzanne anxiously notes days when her daughter eats nothing at all,

and days when she binges and then makes herself throw up.

Then Rachael starts waking up early, locking herself in the bathroom

to cut her legs.

Sometimes she carves entire ugly words in her skin.

The vicious swoops and sharp lines of STUPID bleed over her thigh,

a word that also slices her mother’s heart.

Suzanne, terrified, tries hard to figure out what has gone wrong.

She always tries to wipe up the blood before Rachael's sister awakes.

Several times, a friend helps her search the house for razor blades,

but each one they find is soon replaced by more.

So Rachael (because she cannot yet stop) goes on.

Tokitae survives the hurricane,

but the day-to-day boredom and stress take constant tolls.

Trainers make note of her lethargy, anxiety, and agitation,

of her jaw-popping, skin-rubbing, and stress-chewing.

Regardless, she must (because the show must) go on.

but the day-to-day boredom and stress take constant tolls.

Trainers make note of her lethargy, anxiety, and agitation,

of her jaw-popping, skin-rubbing, and stress-chewing.

Regardless, she must (because the show must) go on.

|

But she is less and less willing to perform before people,

in whose presence she has spent all but four years. She has been removed from her family and confined to a distant fishbowl. |

But she is less and less at ease with people,

though she gives them so much of her time. She feels removed and distant from humankind-- as if outside, looking in. |

She suffers alone, in the silence of self-mutilation.

|

Their cheers and applause at her performances

mean nothing to her; they are only sounds that she hears whenever she follows an order. This is not a show of love or respect. |

Compliments on her performances mean nothing to her;

they are only sounds, empty applause. She feels undeserving of her own or anyone else's love and respect. |

If she could speak the words, she would say

If they only knew.

Some days are better than others; on bad days, she wants to die.

Sometimes she beats her head against the wall, her eyes dull with pain and rage.

She has to keep going; the show must go on; she cannot lie low all day.

So ten years pass by, soaked in blood and sorrow.

If they only knew.

Some days are better than others; on bad days, she wants to die.

Sometimes she beats her head against the wall, her eyes dull with pain and rage.

She has to keep going; the show must go on; she cannot lie low all day.

So ten years pass by, soaked in blood and sorrow.

As gossip permeates her overlapped communities,

Rachael begins to lose all she had gained.

Her childhood best friend is no longer available.

Her church youth group responds to complaints from parents

by asking Suzanne to keep her daughter away.

Worst of all, she loses her prized volunteer role at the Aquarium,

the only role that had been assuaging her sense of shame.

Suzanne and Gary are desperate.

They spend all their time and savings on finding her help.

Suzanne takes her to doctors and therapists hours away.

She reads recommended books about disorders, and attends support groups;

she is encouraging, generous, and kind.

She tries not to cry.

Rejection is anathema to her.

She does everything she can to fill Rachael’s needs,

to show her love, and help her daughter heal.

Rachael begins to lose all she had gained.

Her childhood best friend is no longer available.

Her church youth group responds to complaints from parents

by asking Suzanne to keep her daughter away.

Worst of all, she loses her prized volunteer role at the Aquarium,

the only role that had been assuaging her sense of shame.

Suzanne and Gary are desperate.

They spend all their time and savings on finding her help.

Suzanne takes her to doctors and therapists hours away.

She reads recommended books about disorders, and attends support groups;

she is encouraging, generous, and kind.

She tries not to cry.

Rejection is anathema to her.

She does everything she can to fill Rachael’s needs,

to show her love, and help her daughter heal.

Ever since Tokitae’s cruel capture in 1970,

thousands of people have worked to get her home,

from the Lummi who have lived with the orcas

for thousands of years, and consider them their undersea relations,

to schoolchildren, actresses, rock stars, media magnates, surfers,

PETA, Greenpeace, and the governor of Washington State.

Two of the most influential have been half-brothers Howard Garrett and Ken Balcomb,

founders of The Orca Network, whose dedication and science have led

to a collaborative, Lummi-led plan

to carefully repatriate the orca to Puget Sound,

and have helped bring world attention to her plight.

Publicity has not been positive for Seaquarium,

but the park has always held its ground, claiming such a move would harm “Lolita”--

that she can never learn to fish, and would not know her family.

That it has been too long, and she is far too old.

thousands of people have worked to get her home,

from the Lummi who have lived with the orcas

for thousands of years, and consider them their undersea relations,

to schoolchildren, actresses, rock stars, media magnates, surfers,

PETA, Greenpeace, and the governor of Washington State.

Two of the most influential have been half-brothers Howard Garrett and Ken Balcomb,

founders of The Orca Network, whose dedication and science have led

to a collaborative, Lummi-led plan

to carefully repatriate the orca to Puget Sound,

and have helped bring world attention to her plight.

Publicity has not been positive for Seaquarium,

but the park has always held its ground, claiming such a move would harm “Lolita”--

that she can never learn to fish, and would not know her family.

That it has been too long, and she is far too old.

But so many believe that she can make it.

That she has what it takes, inside and out,

to be well and free.

That she has what it takes, inside and out,

to be well and free.

In 2018, Tokitae is fifty-two. Not young,

Yet surely an orca who can remember an eight-year-old trick when given a long-unused signal

can remember her first four years of catching fish.

Surely an orca who responds to recorded calls, and still sings songs in her pod’s dialect,

can remember her mother and family and culture.

Tokitae must have self-awareness:

She knows from whence she came and who she is.

Yet surely an orca who can remember an eight-year-old trick when given a long-unused signal

can remember her first four years of catching fish.

Surely an orca who responds to recorded calls, and still sings songs in her pod’s dialect,

can remember her mother and family and culture.

Tokitae must have self-awareness:

She knows from whence she came and who she is.

In 2018, Rachel is twenty-four.

Misery and shame have surrendered to courage,

to the aid of her therapist and medications,

to the love of her mother and family.

All of these have helped her become more self-aware.

She knows from whence she came and who she is.

Misery and shame have surrendered to courage,

to the aid of her therapist and medications,

to the love of her mother and family.

All of these have helped her become more self-aware.

She knows from whence she came and who she is.

She is ready to be with people again,

to share her tale with strangers for sufferers' sakes.

Talking outside one night, she holds out her arm,

her cell phone's glow revealing a small tattoo:

brave

the word scripted across her inner left wrist

in lowercase letters with sharp serif hooks,

a blue word in bold, a feminine font

with a hint of hesitancy.

Higher up, the glow illumines scars,

hundreds of raised lines

that span the inside of her arm

like fibers of flax in ivory linen,

woven back and forth from elbow's bend to brave,

the word overwriting this pale palimpsest.

to share her tale with strangers for sufferers' sakes.

Talking outside one night, she holds out her arm,

her cell phone's glow revealing a small tattoo:

brave

the word scripted across her inner left wrist

in lowercase letters with sharp serif hooks,

a blue word in bold, a feminine font

with a hint of hesitancy.

Higher up, the glow illumines scars,

hundreds of raised lines

that span the inside of her arm

like fibers of flax in ivory linen,

woven back and forth from elbow's bend to brave,

the word overwriting this pale palimpsest.

Rachael has made it back; she is well and free.

She attributes self-awareness to her survival, and to Tokitae's, too.

She has thought of the orca every day for the past twelve years,

though she has been too miserable to get involved.

Now, in a burst of empowered compassion,

Rachael is ready to get back to giving,

to actively join the quest to free her friend.

She attributes self-awareness to her survival, and to Tokitae's, too.

She has thought of the orca every day for the past twelve years,

though she has been too miserable to get involved.

Now, in a burst of empowered compassion,

Rachael is ready to get back to giving,

to actively join the quest to free her friend.

In May the Lummi of Puget Sound take a journey

of seven thousand miles to publicize Tokitae’s plight.

They are driving across the nation to meet with her keepers

and demand their relation’s return to the Salish Sea.

Behind them, strapped to their flatbed truck, lies a totem pole

inspired by a young girl with Down’s Syndrome,

a girl far away in New York who had dreamed

of Tokitae crying alone in the Seaquarium pool:

does anyone hear me?

please help me!

does anyone hear?

When the Lummi were told of the young girl’s dream,

their master carver created a sixteen-foot totem that featured her, riding an orca.

This masterpiece accompanies the travelers, and makes the news.

of seven thousand miles to publicize Tokitae’s plight.

They are driving across the nation to meet with her keepers

and demand their relation’s return to the Salish Sea.

Behind them, strapped to their flatbed truck, lies a totem pole

inspired by a young girl with Down’s Syndrome,

a girl far away in New York who had dreamed

of Tokitae crying alone in the Seaquarium pool:

does anyone hear me?

please help me!

does anyone hear?

When the Lummi were told of the young girl’s dream,

their master carver created a sixteen-foot totem that featured her, riding an orca.

This masterpiece accompanies the travelers, and makes the news.

Rachael learns of their journey, and is tempted to go to Miami,

to join up with the Lummi when they reach her soul-sister’s side.

She has long resisted seeing Tokitae in person,

though she reads about her and her species incessantly.

It would be so hard to see the suffering form of her obsession.

But Suzanne encourages her, and finds a way to pay for the trip.

The two take another soul-feeding journey together.

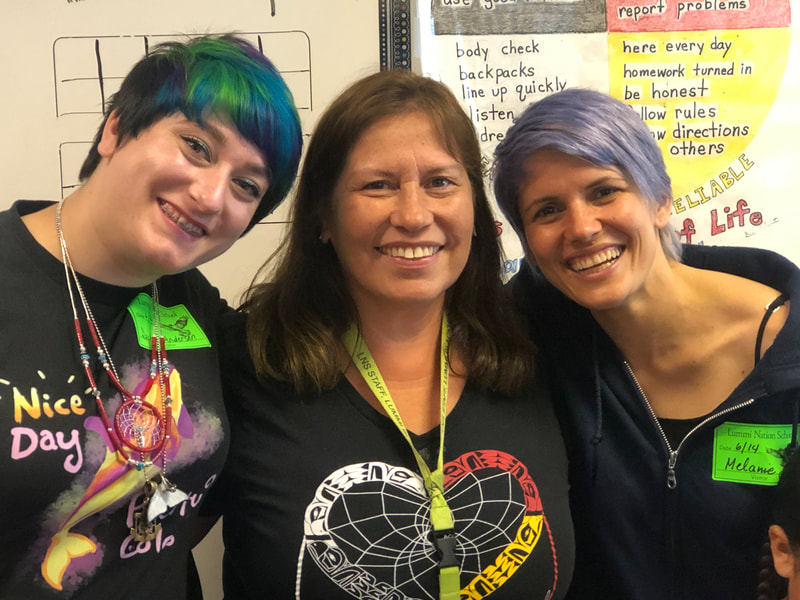

In Florida, Rachael is thrilled to meet

the activists and artists she has ardently admired for years:

the Lummi elders and House of Tears carvers,

including master carver Sit Ki Kadem, also known as Doug James,

who is so touched by Rachael’s earnest passion that he adopts her as his granddaughter;

to join up with the Lummi when they reach her soul-sister’s side.

She has long resisted seeing Tokitae in person,

though she reads about her and her species incessantly.

It would be so hard to see the suffering form of her obsession.

But Suzanne encourages her, and finds a way to pay for the trip.

The two take another soul-feeding journey together.

In Florida, Rachael is thrilled to meet

the activists and artists she has ardently admired for years:

the Lummi elders and House of Tears carvers,

including master carver Sit Ki Kadem, also known as Doug James,

who is so touched by Rachael’s earnest passion that he adopts her as his granddaughter;

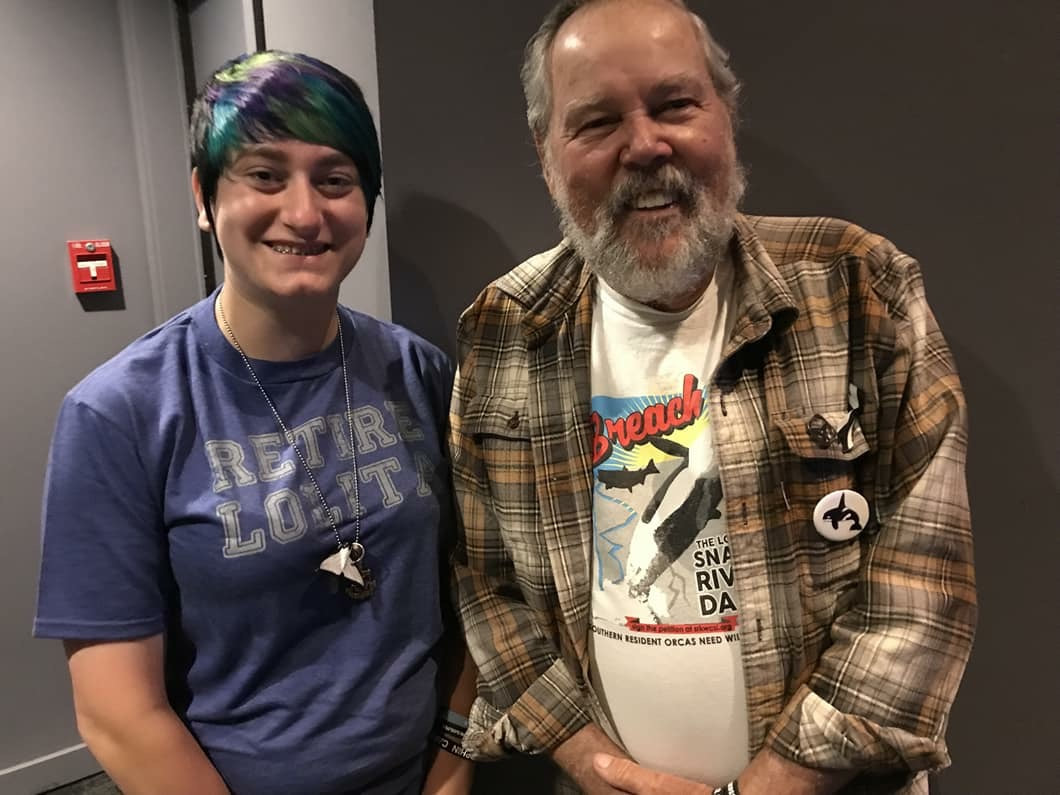

she meets her heroes Susan Berta, Susan's husband Howard Garrett, and his brother Ken Balcomb--

founders of the Orca Network and the Center for Whale Research,

scientists whose marine expertise is globally renowned, and who have created,

with the Lummi (who have renamed the orca "Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut"),

a plan for bringing her home and helping her acclimate.

founders of the Orca Network and the Center for Whale Research,

scientists whose marine expertise is globally renowned, and who have created,

with the Lummi (who have renamed the orca "Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut"),

a plan for bringing her home and helping her acclimate.

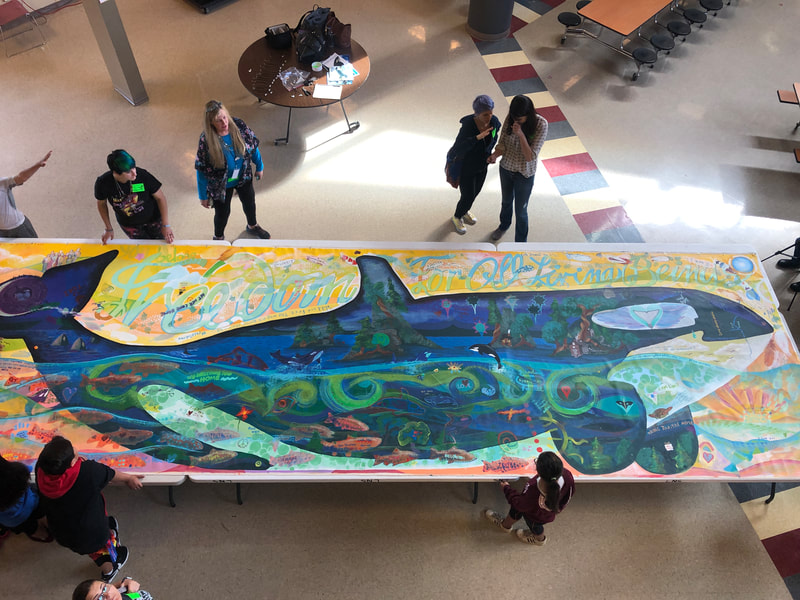

She also meets artist Melanie Schambach,

who is designing a beautiful mural of Tokitae.

Rachael’s thoughts swirl and rise in a wave of ideas.

She suggests the long canvas mural be taken to schools,

so children can add their words and art as well.

Melanie agrees and asks Rachael to make it so,

entrusting the canvas to her from Miami on.

But at Seaquarium, outside the entrance, Rachael balks.

She can’t walk through the door.

You have to, says her mother; that’s why we came all this way.

Rachael’s knees buckle, her stomach roils,

and the air seems as gray as the Seaquarium parking lot.

I can’t.

Come on, Rach, says Suzanne. Your soul sister’s waiting for you in there

who is designing a beautiful mural of Tokitae.

Rachael’s thoughts swirl and rise in a wave of ideas.

She suggests the long canvas mural be taken to schools,

so children can add their words and art as well.

Melanie agrees and asks Rachael to make it so,

entrusting the canvas to her from Miami on.

But at Seaquarium, outside the entrance, Rachael balks.

She can’t walk through the door.

You have to, says her mother; that’s why we came all this way.

Rachael’s knees buckle, her stomach roils,

and the air seems as gray as the Seaquarium parking lot.

I can’t.

Come on, Rach, says Suzanne. Your soul sister’s waiting for you in there

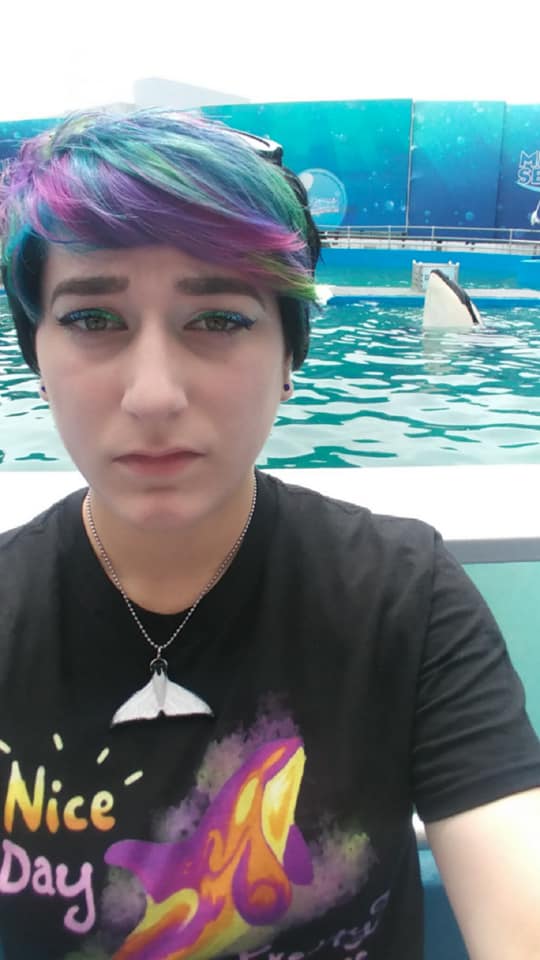

Rachael moves forward, down into the whale bowl.

Pretty, iridescent abalone shades color her hair,

illustrating the words on the shirt she's designed herself:

"Nice day, pretty colors," the translation of Tokitae.

She raises her eyes and dares to look toward the pool.

No sooner does she spot the great black back of her friend,

halfway across a shockingly tiny tank,

than the loudspeaker blares a new song:

Hey soul sister. . .

you gave my life direction . . .

you're . . . one of my kind

The song pulls Rachael forward.

She stumbles down to the railing, and starts to talk.

She doesn’t know what she’s saying, only that she has words she needs to get out,

and that the enormous orca at the “island” in the center

is making a long slow turn,

one eye on Rachael, then

swimming straight toward her,

stopping right in front of her, and

rolling back and fixing her right eye on her,

the long steady gaze of a friend recognizing a friend--

a soul sister.

Pretty, iridescent abalone shades color her hair,

illustrating the words on the shirt she's designed herself:

"Nice day, pretty colors," the translation of Tokitae.

She raises her eyes and dares to look toward the pool.

No sooner does she spot the great black back of her friend,

halfway across a shockingly tiny tank,

than the loudspeaker blares a new song:

Hey soul sister. . .

you gave my life direction . . .

you're . . . one of my kind

The song pulls Rachael forward.

She stumbles down to the railing, and starts to talk.

She doesn’t know what she’s saying, only that she has words she needs to get out,

and that the enormous orca at the “island” in the center

is making a long slow turn,

one eye on Rachael, then

swimming straight toward her,

stopping right in front of her, and

rolling back and fixing her right eye on her,

the long steady gaze of a friend recognizing a friend--

a soul sister.

She looks into her eyes, feeling what she feels too:

It doesn't matter how many people are clapping for you, or how many cheerleaders you have.

It doesn’t matter how well you perform according to expectations.

You can jump through all the hoops imaginable and hit your mark every time,

and no matter how many rewards you earn, you still feel unworthy and sick of yourself.

The desire to be somebody somewhere else is dominant, even if that somewhere is out of this world

It doesn't matter how many people are clapping for you, or how many cheerleaders you have.

It doesn’t matter how well you perform according to expectations.

You can jump through all the hoops imaginable and hit your mark every time,

and no matter how many rewards you earn, you still feel unworthy and sick of yourself.

The desire to be somebody somewhere else is dominant, even if that somewhere is out of this world

It is a transitional moment that will fuel Rachael’s fire forever.

That day, leaving the marine park for the airport,

she is compelled to go back and leave a page of her heart in the bleachers--

a letter, a token of love for Tokitae.

Suzanne does not balk, though the timing is tight,

and the artist’s precious original mural will have to be left in the car, with the driver.

She pays the man extra to get them back to Seaquarium quickly,

and to wait, then rush them to the airport to make their flight.

But when mother and daughter approach the entrance,

they are suddenly surrounded by men in suits and seven police.

Rachael has been identified, perhaps by her abalone-colored hair,

as a known “activist"—that noble person who cares enough to act.

One of the suits is the Seaquarium manager himself.

You will leave immediately and never come back or we will have you arrested, he threatens.

The two women, hearts thumping, turn and leave,

but their activism only ascends.

That day, leaving the marine park for the airport,

she is compelled to go back and leave a page of her heart in the bleachers--

a letter, a token of love for Tokitae.

Suzanne does not balk, though the timing is tight,

and the artist’s precious original mural will have to be left in the car, with the driver.

She pays the man extra to get them back to Seaquarium quickly,

and to wait, then rush them to the airport to make their flight.

But when mother and daughter approach the entrance,

they are suddenly surrounded by men in suits and seven police.

Rachael has been identified, perhaps by her abalone-colored hair,

as a known “activist"—that noble person who cares enough to act.

One of the suits is the Seaquarium manager himself.

You will leave immediately and never come back or we will have you arrested, he threatens.

The two women, hearts thumping, turn and leave,

but their activism only ascends.

Suzanne once again finds a way to get Rachael where she needs to go:

this time to a “Superpod” conference in Puget Sound,

a gathering of thousands of marine mammal experts, conservation organizations,

politicians, reporters, artists, writers, celebrities,

grass roots organizations, schoolchildren, and others—

people who have worked for decades to get Tokitae home.

Rachael, who has taken her responsibility for Melanie’s mural straight to her passionate heart,

holds painting events at the Lummi Nation school.

Though the orca is their sacred relative under the sea,

many of these children have not heard of Tokitae’s story.

Rachael tells them of the capture at Penn Cove,

and reads them a poem she wrote when she was a child.

The teacher suggests the children write one, too.

One little Lummi boy has lost both of his parents,

and has not turned in any assignments for almost two years.

The teachers have allowed this, letting him work out his grief.

They are overcome with tears when he now writes and turns in two poems,

acrostics that plead

bring her back--

she needs to come home.

this time to a “Superpod” conference in Puget Sound,

a gathering of thousands of marine mammal experts, conservation organizations,

politicians, reporters, artists, writers, celebrities,

grass roots organizations, schoolchildren, and others—

people who have worked for decades to get Tokitae home.

Rachael, who has taken her responsibility for Melanie’s mural straight to her passionate heart,

holds painting events at the Lummi Nation school.

Though the orca is their sacred relative under the sea,

many of these children have not heard of Tokitae’s story.

Rachael tells them of the capture at Penn Cove,

and reads them a poem she wrote when she was a child.

The teacher suggests the children write one, too.

One little Lummi boy has lost both of his parents,

and has not turned in any assignments for almost two years.

The teachers have allowed this, letting him work out his grief.

They are overcome with tears when he now writes and turns in two poems,

acrostics that plead

bring her back--

she needs to come home.

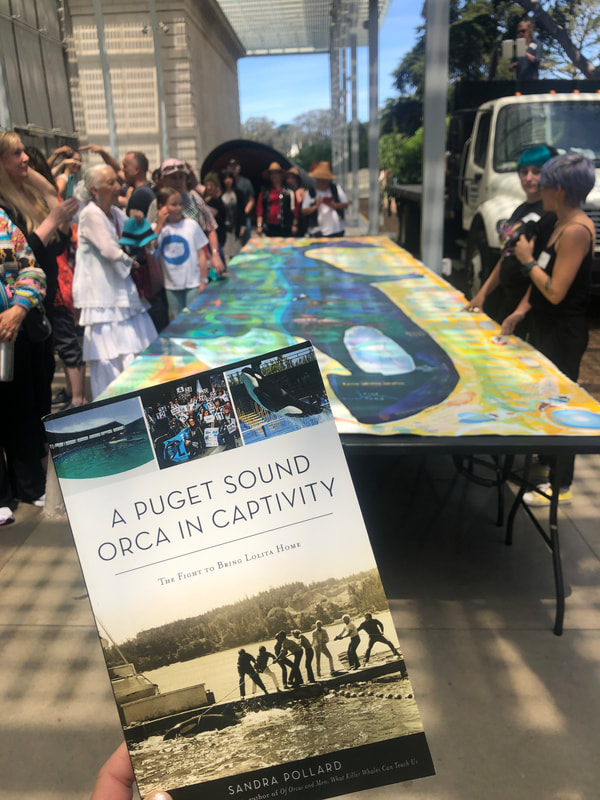

In June 2019, the Andersens host the Lummi leaders,

who are on their way home from their second totem journey to Miami.

(In the Santa Cruz mountains, a sixteen-foot totem pole scarcely turns anyone's head.)

From there, mother and daughter follow their hero-guests back to Puget Sound,

to honor Tokitae and condemn her capture forty-nine years before.

There the completed mural is revealed,

the painting of Tokitae at home in the sea,

a collaboration, thanks to Rachael, between the artist

and activists, children, and teachers all over the continent.

who are on their way home from their second totem journey to Miami.

(In the Santa Cruz mountains, a sixteen-foot totem pole scarcely turns anyone's head.)

From there, mother and daughter follow their hero-guests back to Puget Sound,

to honor Tokitae and condemn her capture forty-nine years before.

There the completed mural is revealed,

the painting of Tokitae at home in the sea,

a collaboration, thanks to Rachael, between the artist

and activists, children, and teachers all over the continent.

At the Lummi school, the orphaned poet reads his latest poem out loud,

his eyes bright with pride: his class sees him now as a hero.

He follows Rachael everywhere, offering to help as she sets up her class presentation.

He adores the young woman whose passion and poetry took him toward wholeness again.

Rachael gives him, and in fact every child, a handmade necklace that looks just like Tokitae’s tail.

his eyes bright with pride: his class sees him now as a hero.

He follows Rachael everywhere, offering to help as she sets up her class presentation.

He adores the young woman whose passion and poetry took him toward wholeness again.

Rachael gives him, and in fact every child, a handmade necklace that looks just like Tokitae’s tail.

Her frame is powerful, sleek and strong.

There’s a sensitive tip of her head that says what words can’t.

She’s beautiful and mysterious, though invisibly ravaged,

a strong survivor sustained by the love of her mother

and of her soul sister.

There’s a sensitive tip of her head that says what words can’t.

She’s beautiful and mysterious, though invisibly ravaged,

a strong survivor sustained by the love of her mother

and of her soul sister.

From Rachael to Tokitae

When I stood by you after the show I told you

how much I love you, that so many are fighting for you.

That you've never been alone or forgotten for a single second...

because SO many people carry you in their hearts,

holding you in spirit through every hurricane-torn storm,

every sun-parched day, and every lonely night

as you cry out, waiting for an answer you never get.

But we hear your cries.

And even if you can't hear an answer or see an end in sight,

help is on the horizon.

We'll never stop until you're

healthy, happy,

and home.

I have made friends, traveled the country,